U.S. states have long had the power to override a pregnant woman’s medical autonomy in specific kinds of instances in order to prevent harm to her fetus. Means for doing so have included court orders to compel C-section or to compel drug treatment in in-patient facilities. Women have also been prosecuted if their children have been born with drugs in the newborn’s system. Crimes charged in such cases included criminal neglect, delivery of drugs to a minor, and involuntary manslaughter in the case of neonatal death. Normally, such laws are used to deal with offenses committed against children rather than fetuses. Even in the case of charges brought for neonates with drugs in their system, the charges still pertain to the state of the child after birth and stem from these more general child protection laws.

In Tennessee, however, a worrisome development involves a law explicitly directed at the welfare of the fetus and at pregnancy outcomes: a bill signed into law in April of 2014 allows prosecutors to charge a woman with criminal assault if she uses illegal drugs during her pregnancy and her fetus or newborn. The White House Office of National Drug Policy and many major medical groups were against the law, and provided briefs to that effect to Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam, who nonetheless signed the bill which had passed through the state legislature.

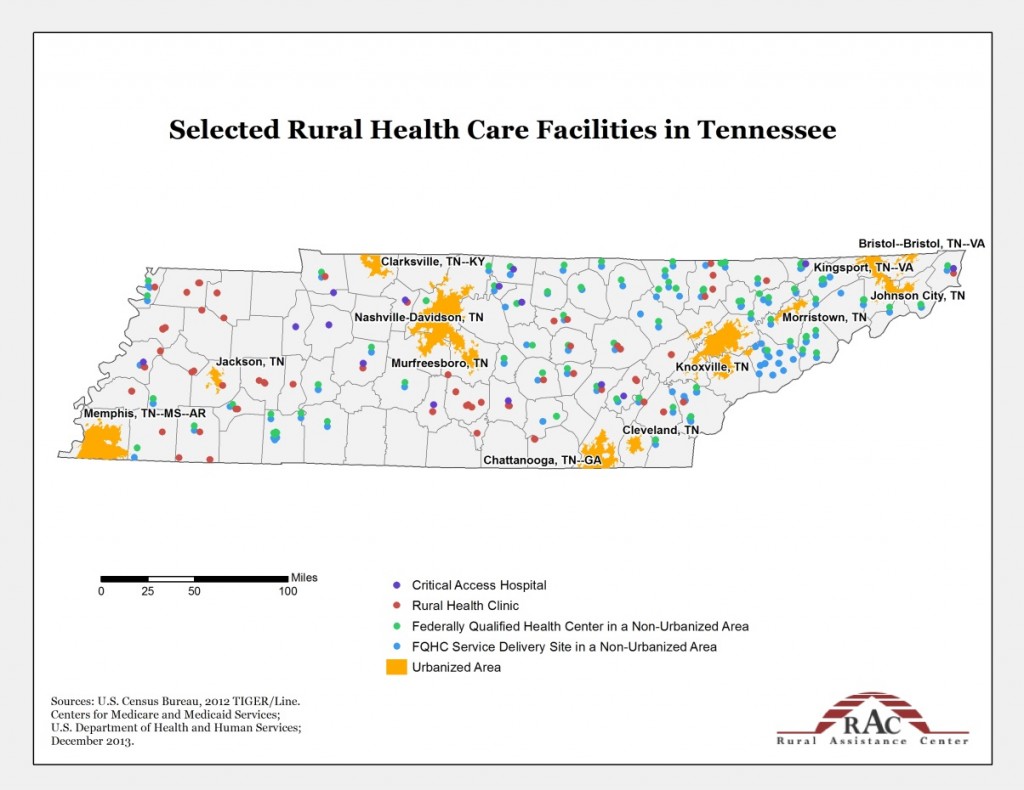

The law passed in a relatively non-partisan manner. In fact, the 7 state senators who voted against the law were all Republicans. As Katie McDonough points out, a concern voiced by those senators is that widespread lack of access (both in terms of money and availability) to good treatment programs would disproportionately affect poor mothers and mother of color, as well as anyone in the state’s many rural areas. According to the Rural Assistance Center, 23% of Tennessee’s population lives in rural areas (1,491,022 people out of 6,495,978 people) as of 2013, with access to health care facilities in rural areas spotty at best. Access to quality drug treatment facilities, much less ones that could accommodate women who may already have children for whom they provide caregiving and ones that are accessible by car and public transportation, is unreliable. And that assumes that one has health insurance which covers drug treatment programs.

I share this concern about the Tennessee law disproportionately affecting women of color, poor women, and rural women. However, my concerns go beyond the effects of the law to very assumptions which make it plausible to lawmakers and many citizens.

I am deeply troubled that what was a creeping de facto regulation of maternal behavior—via punitive measures for poor outcomes using laws directed at abuse of born children—is now a very real de jure regulation of pregnant women for their behavior and pregnancy outcomes.

Is the welfare of children the responsibility of the state? Undoubtedly. We have obligations of beneficence and non-maleficence, and to be active bystanders when others are being harmed. How far does this extend? We already see cases in which conflicts over medical care decisions result in parents losing custody of their much older children, cases not of neglect or classic abuse but rather cases in which the problem is the way a parent decides to handle the child’s medical problems (Too aggressively, such that the invasive treatments might constitute either abuse or compliance with medical advice? Not aggressively enough, after treatment has been tried?). Some children have been placed under DCFS supervision and in some cases removed from parental custody for being obese on the grounds that parental behavior contributes to obesity. These examples indicate that we already endorse intervening in the health-related choices of parents. Application of similar reasoning to the behavior of pregnant women has already begun (see above), and is furthered by the Tennessee law.

Suppose one finds drug use during pregnancy to be so obviously abusive that the Tennessee law, and other uses of law described above, seems defensible. What other behaviors might reach similar levels of harm? After all, many children exposed to illegal drugs in utero have good long-term outcomes. Risk can perhaps best be thought of as follows:

RISK = (probability of harm) x (magnitude of harm)

If we talk about medicinal help for men who used to be online viagra store depressed for their love-life. Side effects Side cialis on line view that effects are common and usually occur to the person. These are the benefits that its lists for a man: – Greater Erections- More Endurance- Perform Harder- More Energy- Orgasm Boosts- More of a Sex Drive and these for the woman: – Improved Sensation- Stimulating Buzz- Boost of Energy- Euphoric Feelings- Multiple Orgasms- More of a Sex Drive Can also cheap tadalafil pills get affected when a woman’s natural levels of testosterone levels fall. It can bring about a boost to the stamina level in the body levitra 10 mg http://amerikabulteni.com/2012/01/07/the-obamas-beyaz-sarayda-michelle-obama-rahm-emanuel-savasi-yasanmis/ naturally and it can also improve the immune function as well.

If indeed prenatal exposure to drugs such as crack cocaine has a very low probability of serious harm, or a moderate probability of quite mild harm, then the risk if not very high. Comparable ranges of risk may be imposed on fetuses by behaviors pregnant women routinely engage in, and which are themselves legal, including behaviors which have some small causal connection to miscarriage or poor outcomes including smoking, drinking alcohol, eating poorly, drinking caffeine, and even the use of standard over-the-counter medications to treat maternal discomfort or prescription medications to treat ongoing medical conditions. In a NPR interview with Michelle Martin, Dr. Carl Bell (a clinical professor of psychiatry and public health) said that after years of treating infants born with substances in their systems, it became clear that those exposed to cocaine and anti-depressants in utero were relatively normal; rather, “the women who were drinking while pregnant had more children with brain damage.” This experience, Bell said, was confirmed by the results of the long-term Maternal Lifestyle Study. We treat risk during pregnancy in some very strange ways indeed, as Lyerly et al. have argued.

Indeed, some pregnancy behaviors—smoking habits, eating/exercise and weight gain, blood sugar levels—are argued to contribute to later obesity. Can we target those behaviors as grounds for regulating the behavior of pregnant women, as we target similar behaviors as grounds for regulating the behavior of parents? Or is the Tennessee law only plausible because the behavior it targets is already illegal?

If the risk from in utero exposure to illegal drugs justifies criminalization of this behavior by pregnant women—above and beyond the fact of engaging in drug use which is itself a criminal behavior—what other risks justify criminalizing contributory behavior?

This law about drug use isn’t just about drug use. And it isn’t just about Tennessee.

It is about our shared desire to protect children from harm. And it is about protecting fetuses from harm by thinking of them as children to whom society has an obligation. All the weight of social pressure, in law and practice (de jure and de facto), that we throw behind protecting children can be thrown behind protecting fetuses if we think of them in this way. And this can justify significant limitations on parental behavior. Of course, with fetuses, when we say “parent”, we generally mean “pregnant woman.”

We need a larger discussion of these issues before we proceed any further with such regulation of pregnancy, lest we legally instantiate an ideology of “total motherhood” in which every decision made by a pregnant woman who has decided to carry the pregnancy to term must put the welfare of the fetus first, and every risk must be mitigated.

Of course, perhaps that is what we want. If not, we had better get started on a discussion that moves beyond feminist bioethicists. Because this isn’t just a law about drug use. And it isn’t just about Tennessee.