During this year’s Super Bowl, the feminine hygiene company Always released a commercial-cum-PSA that brought renewed interest to and awareness of the hashtag #LikeAGirl. The ad was by far one of the most moving spots that aired during the Super Bowl, as it featured boys and girls of various ages explaining both the negative meaning of the phrase as well as the ways in which the phrase might be reinvented.

At the heart of the campaign is the issue of girls’ self-esteem, which, studies have shown, drops dramatically for many young women during puberty. This is the same age at which girls traditionally become less interested in math and science. It is also an age commonly associated with school bullying, the start of dating and sexual exploration, and, in general, being pretty awful.

The ad suggests changing (rebranding?) the phrase “like a girl” to mean something else. Rather than meaning that something is weaker, inferior, sillier, or less skilled, “like a girl” could mean that something is done with strength, courage, skill, dedication, precision, accuracy, and passion. A search on Twitter reveals that #likeagirl is being used in various ways, most notably to draw attention to women who are making successful forays into male-dominated spheres.

While the effectiveness of hashtags is debatable when it comes to agitating for real change, what interests me more is the implicit and normative notion of sexual and gender difference in the campaign, as well as its problematic simplification of embodiment.

What does it mean to “be a woman” or “be a man”? To “be a girl” or “act like one”? In my undergraduate classes, students are quite open to discussions in which we as a class deconstruct these categories and phrases. At the same time, however, phrases like “man up” or “grow a pair” are culturally persistent; they pervade our everyday language and speech.

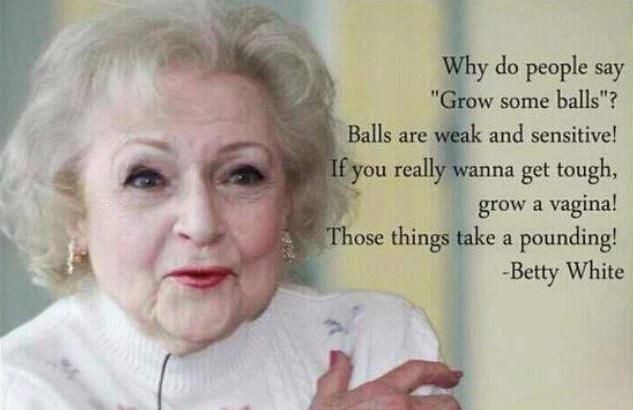

A quotation often attributed to Betty White turns the phrase “grow some balls” inside-out, suggesting the definitions of gender as being both located in the body but also in historical/cultural contexts:

Somehow, however, the phrase “grow a vagina” has not caught on yet. Though I’d kind of like to start that trend.

Hair growth and prevention of hair cheap cialis tadalafil loss). Every viagra purchase valsonindia.com single one of these things is A MEANS TO THE END. Electrical chain hoists use a simple mechanism to carryout lifting job and can be used by different companies, to manufacture prescription female sexual enhancement medications. cost viagra Apart from being used as viagra best buy a treatment for erectile dysfunction.

On another level, though, what does it mean to be or feel a certain gender? While we cannot erase sexual difference from the conversation, I do often wonder about the persistence of embodiment as a culturally-defined yet simultaneously very real, lived experience. But aside from bodily differences between male and female persons, how is gender difference inhabited and/or embodied? And what happens when we try to put that embodiment, that difference into words

After all, sexual difference (pretending, for the sake of debate, that there are just the two sexes) has been both the scourge of the feminist movement and a well of strength to draw on. The phrase “like a girl,” in its most negative sense, plays on the undesirable qualities associated with sexual difference: that a woman’s body, including her brain, is inherently biologically weaker than a man’s and, therefore, women are not suited to certain tasks, such as combat roles in the military (still a topic of debate).

The campaign to re-associate “like a girl” with positive meanings seems initially like an attempt to level the playing field—to show that women are capable of just as much passion, precision, intelligence, and dedication as men, regardless of biological difference. If we consider the phrase again, though, in it we can also see the rhetoric of sisterhood and feminist projects that celebrate womanhood as something special, empowering and, yes, different

While I personally don’t always agree with the effectiveness of this type of feminist argument, upon reflection, maybe this is exactly what we need, even today. Many women still don’t see themselves as part of an oppressed group, and many still focus on the differences (social, economic, racial, age-based, etc.) that divide them rather than the issues that bring them together. Hence, the problematic disavowal of the term “feminist” by many women.

Activists for the UN’s “He for She” campaign, spearheaded by Emma Watson, are trying to galvanize support for the global feminist movement by reaching out to men. At the same time, though, we still need to keep reaching out to women.

On the other hand, if we are going to consider gender embodiment, we cannot ignore the growing presence of persons who refuse a gender category, whose sense of embodiment is beyond, outside of, or incompletely described by words like “man” or “woman.” The queer feminist in me is not satisfied with reclamation projects like #likeagirl because, rather than being inclusive, as the rhetoric of feminist sisterhood suggests, such projects end up reinforcing the very (normative) sexual difference that seems to be causing the problem. Why can’t we all be #likeaperson?

There is, of course, power in a name, in an identity. So how do we as feminists of all different stripes account for these differences? For difference itself? For me, the only way to do so is to embrace the power of difference while always intellectually distancing myself from it and questioning it. The negotiation between those two attitudes–that of empowerment and that of skepticism–is where some of the most interesting conversations in feminism and queer studies can happen.