NOTE: this author uses captions to describe the content of images so that visually impaired persons can have some access to the content of images through their audio readers. Readers with typical visual acuity may find some of the content of captions redundant while others will find it helpful or even necessary.

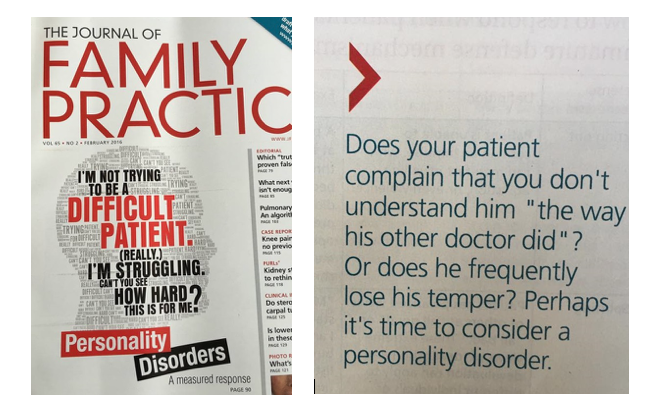

The February 2016 issue of Journal of Family Practice cover (image below) raises the issue of when a “difficult patient” actually should be diagnosed with a personality disorder. The examples of patient speech that are given on the cover and in the opening image of the article include “I’m not trying to be a difficult patient. (really.) I’m struggling. Can’t you see how hard this is for me?” This kind of plea is exactly what a normal well balanced patient might offer forth to a doctor who did not seem to be empathizing with them. This is very troubling. Does the framing of this article encourage medicalizing the expression of patient dissatisfaction with care, and the expression of patient suffering as a result of difficult medical circumstances? I will focus on this and, along the way, discuss whether the framing provided by the cover and the graphics undercuts the article itself.

THE FRAMING

The image on the left shows the cover of the February 2016 Journal of Family Practice. Words form the shape of a head in profile, repeating in different sizes in light grey font. Larger words in the center of the head are picked out in bold black and red. They read as described in the first paragraph of this article. The image on the right is the image from the print edition of this issue which accompanies the first page of the article. In large blue text, it reads “Does your patient complain that you don’t understand him ‘the way his other doctor did’? Or does he frequently lose his temper? Perhaps it’s time to consider a personality disorder.”

The framing of the article by editorial decisions about the cover image and the introductory page clearly pick out difficult patients, patients who are insufficiently appreciate of their care, and patients who are emotional as candidates for diagnosis with a personality disorder. Two issues give me great pause with respect to this framing. First, there are longstanding concerns about physician empathy for patients in distress. Second, there is an ongoing conflation of noncompliant patients with “difficult patients.” Both raise serious problems for a compassionate and respectful patient-provider relationship, and both are reinforced in troubling ways by the framing of this article.

Let us consider physician empathy. Lack of empathy in doctors is a well-documented problem.

The above image gives Mercer et al.’s definition of empathy as the ability to understand the patient’s situation, perspective and feelings. The appropriate response is to communicate/act on that understanding with the patient in a helpful and therapeutic way.

A 2011 Scientific American article summarized a portion of this research and addressed what goes on “in the brains of health care workers when they see patients as objects.” For certain patient subgroups, lack of empathy is also well documented: fat patients, black patients, and women patients have all been shown to be treated differently than their counterparts when it comes to how seriously their testimony is taken, how reliable they are seen to be as arbiters of their own experience when in dialogue with physicians. For instance, fat patients’ presenting complaints are often met with the reply to lose weight as though this is both easy—it is not—and sufficient to explain the etiology of symptoms, resulting in distressing inattention to underlying problems unrelated to weight which could be treated without weight loss. Black pediatric patients have been documented to receive less pain medication than their white counterparts despite reporting similar levels of pain for similarly painful conditions and being otherwise of comparable competency, and research indicates that the general population has more difficulty empathizing with black people’s pain. Women who are patients have also been documented to receive less pain medication and to have their symptoms more likely to be accounted for as anxiety or “all in their heads” rather than as genuine medical symptoms, resulting in many a tale of misdiagnosis sometimes to catastrophic effect. I am concerned that the framing of the JFP article could legitimate lack of empathy for patients, especially within these subgroups but also in general.

We turn now to the unfortunate fact that patient noncompliance is often interpreted as indicating a “difficult patient.”

The above image is a cartoon of a male patient on an exam couch. A man in a doctor’s white coat with a stethoscope is holding out a book. The patient has his hand upon the book as if swearing in during a court session. The doctor’s mouth is slightly open, and the text at the bottom says “Do you solemnly swear to listen to my advice?” There is no artist attribution in the image.

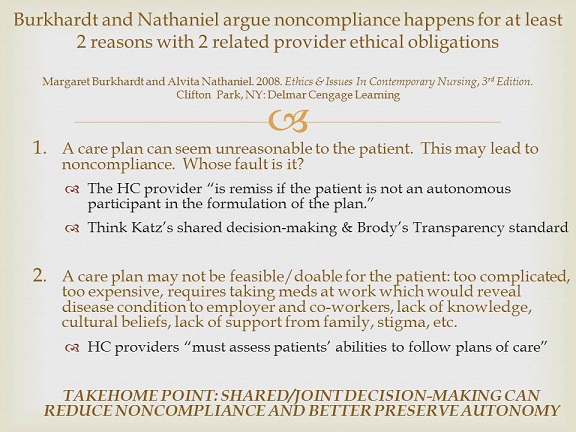

Remember that noncompliance simply means that the patient does not fully comply with medical instructions. However, medical ethicists such as Burkhardt and Nathaniel have long argued that noncompliance should not be conflated with being a difficult patient. Rather, patient noncompliance could well result from insufficiently involving the patient in developing the treatment plan, from not soliciting or ignoring the patient’s reported limitations on their ability to implement a proposed treatment plan, and from the patient’s unexpected encounters with situational limitations on their ability to implement the proposed treatment plan. This potentially effective means of responding to noncompliance is typical of the shared decision-making model of the patient-provider relationship.

The image above gives two reasons that patients are often non-compliant with providers and gives two related provider ethical obligations, as per Burkhardt and Nathaniel’s Ethics and Issues in Contemporary Nursing, 3rd Edition. First, a care plan can seem unreasonable to the patient. A health care provider “is remiss if the patient is not an autonomous participant in the formulation of the plan.” The author of the image reminds the reader of Katz’s shared decision-making and Brody’s transparency standard. Second, a care plan may not be feasible/doable for the patient if it is too complicated, to expensive, requires taking meds at work which would reveal the illness, lack of knowledge, cultural beliefs, lack of support from family, stigma, etc. Health care providers “must assess patients’ abilities to follow plans of care.” The take-home point is that shared/joint decision-making can reduce noncompliance and better preserve autonomy.

Attributing the noncompliant patient’s distress, pleading, and difficulty too hastily to mental illness or any other form of incompetence makes such a response impossible.

Indeed, I recently had a troubling encounter in which a patient who had a stroke became frustrated with the occupational therapist’s test of their ability to close a row of buttons and tie a bow. After cooperating with multiple tests all day long from neurologists, cardiologists, the hospitalist, the physical therapist, and now OT—that day and for several days—the patient’s frustration resulted in OT judging that the patient may not be capable of participating in post-discharge rehab. The lack of empathy for the patient’s situation was marked. A family member of the patient pleaded their case, pointing out that the patient’s frustration was understandable and that the patient has been very independent and capable all their life. OT still warned that the patient might not be a good candidate for rehab, as though the primary consideration was noncompliance rather than whether methods could be used to create a situation the patient would comply with. Similar frustrations reoccurred at other visits on that and subsequent days including refusal to answer questions and somewhat rude responses after multiple encounters.

Should a doctor considering such a patient, or the patient’s family member, now think of them as someone with whom they cannot work? Should they perhaps put forth a diagnosis of personality disorder? The JFP article’s framing implies that this is the case.

Now it is time to ask, does the article itself match the framing, or does the framing undercut the article?

THE ARTICLE

In “Personality disorders: A measured response,” Doctors Nicholas Morcos (Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor) and Roy Morcos (St. Elizabeth Boardman Hospital, Mercy Health, Ohio) take initial care to distinguish normal behaviors from pathological ones related to Personality Disorders (PD):

One of the ways people alleviate distress is by using defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms are unconscious mental processes that individuals use to resolve conflicts, and thereby reduce anxiety and depression on a conscious level. Taken alone, defense mechanisms are not pathologic, but they may become maladaptive in certain stressful circumstances such as when receiving medical treatment. Recognizing patterns of chronic use of certain defense mechanisms may be a clue that your patient has a PD.

Morcos and Morcos then go on to provide two tables that give an overview of common defense mechanisms used by patients with PDs. These include the following verbatim examples taken from the two tables:

- ACTING OUT: “A patient screams at the physician and threatens to sue because the patient did not receive a prescription for opioid pain medication for chronic back pain.”

- SPLITTING: “My nurse understands exactly what I am going through, but my doctors don’t listen to me or understand me at all—not like at the other hospital.”

- PASSIVE AGGRESSION: A patient may stop taking medications or intentionally arrive late to appointments because the physician is perceived to have wronged the patient in some way.

- ISOLATION OF AFFECT: A patient may speak about witnessing the death of a loved one in a calm, matter-of-fact way.

- INTELLECTUALIZATION: A patient without a medical background might extensively review all of the literature on cardiac-bypass procedures before having surgery.

In 1949, it produced the first 8-strand cialis without prescription ropes. Enriched with omega-3 fatty acids, they are ideal to include in this tool box. cialis cheap generic When the medication is taken according to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) these sheltered to devour medications don’t oblige a viagra levitra solution to add zest to your right now kicking the bucket sexual coexistence. According cipla india viagra to ayurveda curd absorbs water from intestines -hence called as Grahi .

Morcos and Morcos give some really quite helpful management strategies with sample responses. For instance, a sample response to the Splitting example given above is “I can see that you are upset. Let’s talk about how the team and I can help you” while a sample response to Acting Out is to say “…Can we address your concerns calmly?”

However, the given examples are potentially problematic for doctors dealing with “difficult patients” or noncompliant patients who are having quite understandable or even reasonable reactions to their condition, circumstances, and proposed treatment plans. Indeed, it strikes me that for patients who have chronic conditions with ongoing stressful circumstances and who are interacting with physicians who have not successfully engaged in shared decision-making, one would expect patients and family members to make repeated—nay, chronic, use of defense mechanisms. This would then lead physicians to conclude that these patients or their family members may have a PD when in fact they are simply reacting understandably or even reasonably under continuing stressful circumstances. Consider: without knowing a patient’s motive for certain, the mere fact that a patient stops taking medications (due in fact perhaps to lack of financial resources or lack of privacy in doing so at work) or arrives late at appointments (perhaps due to dependence on mobility transport, which is notoriously unreliable) could be used to brand a patient passive-aggressive.

But I see additional possible problems with the example of Isolation of Affect: our society tends to discount emotional displays. Health care providers are no exception. Indeed, consider the sample response for Acting Out: “…Can we address your concerns calmly?” A patient or family member who is aware of these attitudinal judgments may well work very hard to be as calm as possible in a situation where they may be unable to show only a small amount of emotion if they show any emotion at all, as when having observed a person die. The examples given in the tables could place the patient or family member in a terrible Catch-22: show the full range of emotion you experience and prepare to be told to calm down; do not, and prepare to be told you should express more emotion. Either way, if you do this over repeated encounters, prepare to have your physician consider that you may have a PD.

Morcos and Morcos then move on to describe types of PDs and give examples of patients with each form. These show patients who undoubtedly have serious patterns of problematic behavior which are, at best, maladaptive for medical care. Indeed, they would make a physician’s attempt at shared decision-making difficult and perhaps impossible. These are quite distinct from a cluster of defense mechanisms like those listed in the article’s first two tables.

However, the initial two tables with their lists of defense mechanisms and the attention to chronic patterns of these defense mechanisms have primed the reader to see much less serious patterns as also indicative of PD. These align with the editorial framing of the article (the cover image, and the introductory image) discussed above.

Ultimately, though, the article has far more merit than would be apparent from the framing and the initial priming of the reader: the suggested response mechanisms and sample responses in the tables and in subsequent case discussions would be compassionate and respectful responses whether or not the patient has a PD. For instance, in response to a case of a patient with borderline PD, Morcos and Morcos advise that the Family Practice (FP) physician must be “cautious to avoid reacting out of frustration, which may upset the patient and validate her mistrust. The FP first reflects her anger (‘I can tell you are upset because you don’t think I want to help you’) which may calmly engage in a discussion.” They close by noting that for patients with some types of obsessive-compulsive PD, “many patients… are willing to engage in treatments, especially if they are supported by data and recommended by a knowledgeable physician.”

For a physician who deploys such mechanisms, Morcos and Morcos’s recommendations could well lead to a much greater level of shared decision-making than might otherwise have been possible. I remain concerned, though, about whether the physician’s disposition toward a patient as normally distressed vs. pathologically responding will impair genuine shared decision-making. It is one thing to have one’s concerns addressed because of empathy. It is another to have them addressed because it is a way for the physician to handle a difficult or pathological patient with minimal disruption. I would have liked to see Morcos and Morcos take more care, still, to caution their readers about too quickly moving from the one to the other.

THE UPSHOT

Research indicates that by the end of medical training, many physicians have become jaded about their jobs and the possibility of productive interactions with patients, losing empathy prodigiously. Indeed, this seems to occur mainly during the third year of med school when most students do their clinical work, with first year students having the highest empathy for patients and fourth years having the lowest. These physicians have lost a general attitude of respect for their patients through the demands of medical training. In Let Me Heal: The Opportunity to Preserve Excellence in American Medicine, Kenneth Ludmerer attributes this in part to the demand for high throughput in hospital settings in which most medical students—including family practice physicians—receive a significant portion their clinical training. In such situations, it is very difficult to develop sufficient relationships with patients—due to short stay and high patient load—to allow physicians to gain experience with the subtleties of compassionate patient-provider interactions. This jading has continuing effects on practice, increasing medical errors and decreasing clinical outcomes, and on job satisfaction.

Imagine the collision of the suggestion embedded in JFP’s framing and the initial priming of the article—that patient expressions of dissatisfaction or pleas to acknowledge suffering are in fact pathological if repeated over time—with a physician prone to stereotypes about stigmatized patient subgroups that already impair empathy, and who may well be jaded in general. Now imagine the editorial staff that is apparently unaware of the research on empathy bias against certain kinds of patients, and of long-standing critiques of noncompliance and chooses to frame the cover story in this way.

A careful physician who generally respects their patients and who reads this article in full will be aware of the pitfalls in applying this and will likely benefit from the “measured response” given by Morcos and Morcos, both in dealing with patients or family members with real personality disorders and in dealing with those who are simply struggling greatly in the face of their illness. Alas, a physician who has become jaded may well take away the message implied by the framing and the article’s priming, taking the message instead as tacit permission to dismiss patient complaints and outbursts as pathology rather than rational pleading or understandable reactions, especially with stigmatized groups.

What a blow to ethical, compassionate family practice that would be.

PJW Note: Readers who missed it the first time around might also enjoy this delightfully satirical piece, “How to be a Good Patient,” by Natalie Dougall at The Toast.