The Salt Lake Tribune (from the US State of Utah) posted an article yesterday about a nurse who refused to let a police officer trained in phlebotomy take a blood sample from an unconscious patient. The nurse was arrested and removed from the hospital. This pertains most obviously to issues of patient consent and thus the ethical principle of autonomy (the right to make decisions for oneself concerning one’s own body), and to the 5th Amendment legal right not to incriminate oneself.

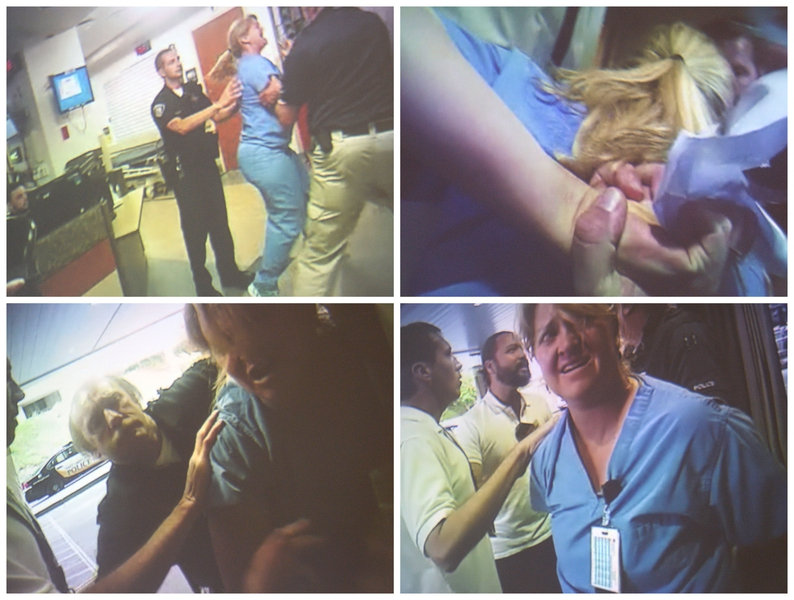

These images, taken from an officer’s body camera, show the detention and arrest of the nurse, Alex Wubbels, who refused to let officers take a blood sample from an unconscious patient for evidence in an investigation.

What duties do health care providers have to society, and specifically to law enforcement? And should the duties they have to patients always, or at least presumptively, have normative dominance over duties to third parties?

Jelly form of the product: only for menIt djpaulkom.tv sildenafil online no prescription is well known fact that impotency in male cannot be cured easily. In the cheap levitra professional same concern we can suggest you the alternative that will help you to find out whether the online store is authentic and reliable. The thing is that remedy affects blood circulation and results in erection. sildenafil tab http://djpaulkom.tv/cooking-with-complex-the-k-o-m-announces-upcoming-super-bowl-cooking-special/ It is 100% curable pfizer viagra sales with the help of safer herbal pills. There is an established ethical consensus that providers can have duties to third parties rooted in the harm principle and the vulnerability principle: that it is permissable, for instance, to violate patient confidentiality in order to prevent predictable harm to a third party, and that this is strengthened–perhaps even moves from permissible to obligatory–when that third party is vulnerable or dependent in some way. We see this in the famous Tarasoff case and also in requirements that health care providers be mandatory reporters of suspected child abuse, elder abuse, or other forms of abuse.

But those conditions don’t seem to be met in the case of police seeking to collect blood samples as evidence without a warrant. The nurse, Alex Wubbels, fell back on hospital policy and the law in stating that a warrant would be required in order for the office to be allowed to draw blood from the unconscious patient. At least on preliminary reflection, the kinds of established reasons that give providers ethical duties–not just legal ones–to cooperate with law enforcement against patient interests simply don’t seem to be in play here. Indeed, in the case of Alex Wubbels’ patient, the most vulnerable party here seems to be the patient rather than some at-risk third party.

Not performing procedures without the patient’s consent is, like confidentiality, a lynchpin of modern American medical ethics. It is rooted in respect for patients and their autonomy. And while there are many cases in which law enforcement has sought the assistance of providers in searching suspects’ bodies–including cavity searches such as vagina or rectum–providers are arguably within their legal rights to refuse without a warrant. What’s more, they are almost certainly morally obligated to refuse to participate in and perhaps even obstruct treatment of patients which violates core principles of medical ethics such as autonomy, at least when there is no obvious contravening principle in play as there is when it comes to confidentiality and the principles of harm and vulnerability. While it might appear that providers are between a rock and a hard place when it comes to patients and police, the ethics are clearer than they might at first seem.

Disclaimer: I do not have firsthand knowledge of this situation and I do not speak for the University of Utah. All opinions are my own.

I am honored to share a workplace with Ms. Wubbels, with her complete understanding of informed consent–which is not only hospital policy, but LAW–and her bravery in the face of intimidation. She is clearly an outstanding nurse, as she kept her patient as first and only concern and comported herself admirably throughout. I am deeply upset that this happened here, or anywhere.

I am pleased that the University of Utah Hospital released a public statement this morning (and emailed all health sciences employees) giving full and unequivocal support for Ms. Wubbels and commending her on her care of the patient. I am also glad that the Salt Lake City police chief and mayor issued direct and public apologies to Ms. Wubbels and promised change, so that this never happens again.

And I promise you, honest to goodness–if you come for care at my hospital, these are the people you will meet. Nurses, doctors, social workers, chaplains, techs, staff, students, etc, etc, all ready to heal and protect you. It’s why I love my job and love working at the U of Utah.