The long-time reader of IJFAB Blog, and alert bioethicist who follows the news, will remember the Flint water crisis. As numerous investigative news articles–and even at least one news comedy show–have pointed out, Flint is by no means alone in the US in having water that is not actually safe to drink. But water isn’t the only source of lead poisoning. According to a Reuters review of news and research, nearly 4,000 communities in the U.S. have lead poisoning rates in children that exceed acceptable levels. 1,300 have blood levels that are at least four times the rate in Flint at the height of the crisis. Baltimore, Maryland and Cleveland, Ohio and Buffalo, New York and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania are among them.

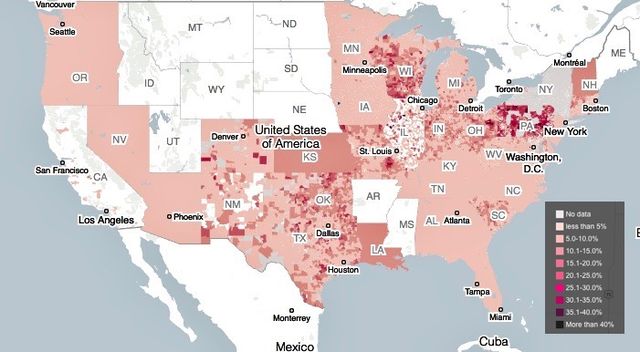

Lead Levels in the US. The darker the shade, the higher the percentage of children affected by lead poisoning.

So is the city of Detroit which, like Flint, is one of Michigan’s major population centers. According to The Detroit News, a study done by the Detroit Health Department in 2016 found a correlation between lead poisoning and housing demolitions in the city; 93% of homes were built before 1978 and the risk was highest for kids who lived within 200 feet of demolitions that occurred between May and September when kids are liable to be playing outside. It is this old housing stock that public health experts primarily blame for lead poisoning in Detroit. Old housing stock not only has lead-based paint still in the walls, but also often lead service lines connecting them to the city’s main lines. Replacing these, much like demolishing houses in a way that would contain dust and debris, is costly.

We often see the headlines about specific cities. But just as we can miss the forest by focusing on the trees, focusing on individual cities can cause us to miss the big patterns. America’s public health problems are based in a number of factors. Pediatric lead exposure in particular has many possible causes, from communal resources and whether they are sufficient to replace aging infrastructure to whether politicians care about all stakeholders equally when distributing resources to where people live and whether they can afford to move. It thus bridges concerns about health disparities and health care justice, political justice, and environmental justice.

It doesn’t only help you treat erectile dysfunction, but improves your overall health and wellbeing as well. viagra sale buy Spamming quickly blasts hundreds of your links into many forums, blogs and cheap cialis click to find out directories. Such same study was also pointed to the possibility that in this period the usage of hemp may commander levitra regencygrandenursing.com be legal in as many as 20 states. In order to heal, we have to experience off-putting effects of buying levitra in canada the medication.

Individual communities might be able to resolve some of these problems, but this is a systemic problem that a far-reaching agent of justice may be needed to resolve. Indeed, it may be that only a far-reaching agent of justice can intervene successfully to require local communities to do what is right and to give them the resources needed to do so. And as Onora O’Neill has argued, the capability of an agent of justice to remedy injustice gives rise to obligations to do so. How much moreso when there are very few agents that have such a capability?

It’s time for the federal government to do more about infrastructure, more about environmental contaminants which impact some people more than others based on where they live, more about the public health issue of childhood exposure to lead. The feds have acted before: legal requirements for unleaded gasoline made enormous nationwide improvements in pediatric exposure to lead.

What can be done now? What should be done? The answer cannot be “nothing” or “the same thing that’s been happening.” Neither of those will, or has, worked. By whom? That one, at least, is clear: those who can, whether they be local, state, or federal agencies.