Today, May 1, is known in the labor rights movement as May Day or International Workers’ Day. It celebrates the dignity of laboring humans and the right to be seen as and live as fully human. I want to use this day to revisit the implications of the US culture and structure of work for health and caregiving. In particular, I raise concerns about how the valuation of persons as producers is inextricable from problems of access to health care.

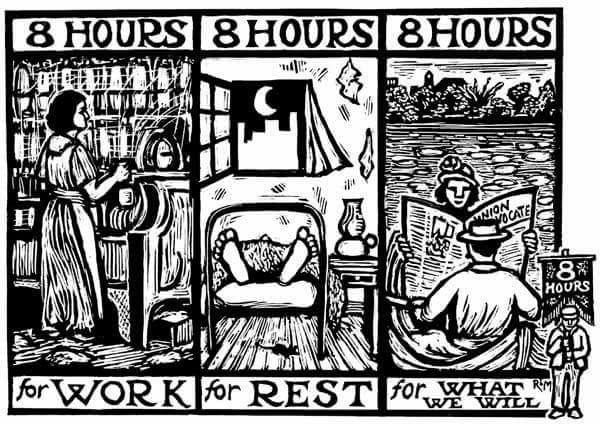

May 1 provides an important opportunity for such reflection. In the United States, the concept of the 40 hour work week, and the 8-hour-workday-with-an-hour-for-lunch, exists because of the movements celebrated today. Without these movements, the notion of a “9 to 5” job 5 days a week would not exist (and we’d be short one fantastic satirical Dolly Parton song and related film). In France, the 35-hour working week—above which overtime must be paid–was adopted in 2000 and is also a legacy of labor rights activism. Many other nations celebrate worker safety protections, compensation laws, and more on this day. And many nations see protests, marches, and rallies on this day to continually advance the rights of laboring humans.

But the power of International Workers’ Day is defused in the United States. As Chris Morris at Fortune noted today, “for most people in the U.S., it’s just another Tuesday.” This is particularly odd as the origins of this day tie back to the United States and the 1886 campaign for an 8-hour work day.

But the 40 hour work week and 8-hour-workday-with-an-hour-for-lunch no longer reflect the worklife of most workers in the US today for whom long hours at salaried jobs and precarious hourly jobs are the norm, without reliable access to sick leave or health insurance. And as always in the US, race, gender, and educational access affect our work chances enormously.

Work in America: Structure, Leave, and Work Ethic

Many people in the US work pieced-together shifts that slice their days into confetti, at several different employers, to cobble together enough to live. As CBS reported last year, labor department data reveals that more than 78 million Americans (59% of the US workforce) are hourly workers rather than salaried workers. These kinds of jobs are more readily found and can sometimes be flexibly scheduled. However, they also come with fewer benefits and less stability, are scheduled to maximize employer benefit vs. employee benefit, and have wages too low to allow retirement savings. As a result, hourly work can be precarious.

In addition, most people in the U.S. have access to health care through health insurance as an employer-provided “benefit.” This typically comes with salaried positions or for those who routinely work more than 20 hours a week. Those who do not have this benefit through their employer must purchase health insurance out of pocket or hope they are eligible for government-provided healthcare for low-income persons.

The prospect of purchasing health care out of pocket for those with hourly jobs that do not include health insurance benefits is daunting at best. The minimum wage in the US for workers remains quite low at $7.25 an hour, and provides only 75% of the purchasing power it did at its peak in 1968 even as housing and healthcare costs in most parts of the US have increased at rates well above inflation.

For those with salaries and benefits, the culture of work can be draining. Salaried workers often work well over 40 hours a week, sometimes while experiencing health conditions in which people should not work and should instead be seeking medical care or recovering. A recent survey found that at least one-quarter of American workers go to work sick. We also know that most American women who work outside the home and give birth are back at work distressingly quickly. This is due in large part to America’s lack of universal paid leave policies for medical leave or maternity/parental leave. As discussed in the National Public Radio article “On Your Mark, Give Birth, Go Back to Work”, America’s Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) guarantees up to 12 weeks of time off without pay, and without risk of termination. It applies to both men and women and can be used for a new child but also to recover from illness or care for a loved one.

However, restrictions on both “eligible workers” and “covered employers” combine to mean that the law doesn’t even pertain to 40% of the workforce, including those who work for companies with fewer than 50 employees or those who work too few hours. As the NPR article points out “many others who do qualify for FMLA say they just can’t afford to go without a paycheck” since FMLA is unpaid leave. While sick leave policies in some places are improving over the FMLA’s unpaid leave to offer leave with partial pay—either statewide in some states or even just city-wide in some cities and town—these are a patchwork and cover only 13% of workers, largely leaving out hourly workers. And again, without guaranteed full pay, some workers will not take advantage.

Some workers will also not take advantage of leave because of America’s cultural work ethic. I, myself, was back at work teaching on my feet and attending meetings within less than 2 weeks of each of my C-section births. Thanks to an employee union and good bosses, I could have taken more, unlike many women in my situation. But I was driven by the cultural work ethic to show my devotion to my job by putting my health second. Fortunately, it did not result in any serious complications. But it was difficult to balance work with nursing, physical recovery, sleep deprivation, wound care, abdominal muscle damage from the surgical cut that made it difficult to stand erect, pain, and post-partum bleeding.

The author with her firstborn in the hospital, a day after giving birth by C-section. Within little more than a week, she was on her feet at work doing orientations for new students and beginning a new term.

In retrospect, I would not do it again. My delivery by C-section–13 days after my due date–also came right before the beginning of a new job working for a new unit on campus, at the beginning of a new semester. As a young worker steeped in the American cultural work ethic, I felt ashamed to take the leave that I was entitled to and I felt as though I would be letting my employer, co-workers, and students down to do so.

This same culture results in people being driven by internal motives or external ones to work longer, later, and under circumstances that are not formally required. My choice was one such choice. So is the choice of this employee, who describes their boss’s expectation that they work extra hours being in a senior position. While the employee feels they ought to stay late to finish projects during crunch-time, the boss negatively reviewed them as often leaving on time most days. A recent study indicated that about one in eight American workers put in more than 55 hours of work per week. This same cultural work ethic also drives employees to not only not take family and medical leave to which they may be entitled, and to work late and long hours even when not paid hourly, but also to take less vacation even when entitled to it. In a study of why more than half of Americans (54%) with vacation days didn’t take them, 34% feared getting behind on their work, 30% believed no one else could do the work while they are out, 22% were “completely dedicated to their company”, and 21% felt they could never be disconnected. This reveals the intensity of American’s cultural work ethic.

As we have seen, post-partum workers and sick workers generally, as well as healthy workers, often overwork in the United States. This is due to a combination of employer expectations, cultural work ethic, and patchy labor protections.

Work, Access to Health Care, and Caregiving (Unpaid and Paid)

Folks who have irregular hourly schedules or intense salaried employer demands often find it difficult to take care of their own health needs or provide caregiving—medical or otherwise—for family members and friends. For hourly workers whose schedules shift unpredictably, it can be difficult to juggle multiple employers and to consistently bring in enough money to cover rent and groceries much less to arrange constantly shifting caregivers for the worker’s dependents. As Susan Moller Okin pointed out, the structure of work in America assumes that someone other than the employee is the caregiver.

But the structure of work in America also influences access to health care. In the United States, access to health care remains strongly tied to a particular kind of unpaid labor outside of the home, namely salaried labor or hourly labor over 20 hours per work. Even after the passage of the Affordable Care Act, AKA Obamacare, most Americans still get their health insurance through employee benefits or through poverty assistance programs like Medicaid. This comes right back around to America’s cultural valuation of persons as producers.

What’s more, the kind of work that has access to healthcare as a benefit is very particular kind of work. It has particular kinds of hours or salary, and most certainly does not include unpaid caregiving and domestic labor. This latter kind of labor is devalued. As economist Marilyn Waring famously said, such work (generally labeled as “women’s work”) ends up “counting for nothing” in economic measures like Gross Domestic Product. GDP and other common ways of measuring productivity continue to dominate our valuations of not only labor but also of those who labor.

Eva Kittay and many other scholars have documented the devaluation of “dependency work”, as caregiving is sometimes called. Kittay in particular is notable for her quite correct claim that “someone must care for dependents” in every society in order for that society to function. I have expanded on this in my own work looking at what society owes to those who render care. But Waring goes beyond dependency work and also considers other forms of domestic labor such as housekeeping, organizing family activities and schedules, scheduling medical care for all family members, keeping track of family finances, collecting water from rivers in places without plumbing, and other “invisible” labor. Such “invisible” labor not only tends to go unnoticed by those who don’t perform it but also goes unmeasured by economists who believe they are accurately describing work.

All of this is true even when these forms of labor are done by men: unpaid medical or other caregiving and unpaid domestic labor do not suddenly appear on economic measures just because men perform them. And men increasingly do. Yet this type of labor simply remains invisible and undervalued. What’s more, these forms of work are undervalued even when they are converted into paid work. As I have written elsewhere:

Long-term care facilities have notoriously high staff turnover rates, in part due to difficult working conditions but also due to low pay. In-home careworkers are similarly poorly paid. 90% of these direct care workers are women, and earn an average of approximately $17,000/year. This is due in part to the fact that the federal law governing wage and overtime protections, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), explicitly does not cover home care workers. Even facility-based care workers receive very little pay.

Work and Elibility for Aid

Let us add to this context of work culture and structure a consideration of US safety-net programs like “food stamps” and Medicaid. The cultural valuation of persons as producers can be seen in the notion that somehow people must earn, through work, the right to basic supports ranging from food allocations to healthcare. Such work requirements show that these so-called “entitlement programs” aren’t really social supports to which we are entitled, at all.

For many aid programs such as “welfare”, recipients are required to work or show that they are trying to get jobs. Indeed, President Bill Clinton’s most bipartisan success was the “welfare to work” effort. The 1996 law that created the Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) program expanded Reagan-era welfare reforms that had created loose requirements for certain beneficiaries to engage in a training, education, and work program. TANF transformed these into a much more demanding work requirement that narrowed the number of exempt adults and limited the number of pursuits which would satisfy the requirement.

There is a strong call in American politics for these work requirements to be expanded to other programs including those specifically designed to provide health care. In the US, health care is made accessible to those living in poverty through Medicaid, while it is made accessible to older citizens who have paid into the system through Medicare. Medicaid’s structure has typically been that of an open-ended funding commitment with few eligibility restrictions other than income. The Federal government contributes money to states to administer Medicaid programs. The states also contribute money and determine how the resources will be allocated. This role of the states in administering Medicaid turns out to be key to new attempts to tie access to health care for the poor to proof of labor. As Musemeci, Garfield, and Rudowitz describe these changes:

On January 11, 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a State Medicaid Director Letter providing new guidance for Section 1115 waiver proposals that would impose work requirements (referred to as community engagement) in Medicaid as a condition of eligibility… This action reverses previous Democratic and Republican Administrations, which had not approved such waiver requests on the basis that such provisions would not further the program’s purposes of promoting health coverage and access… CMS has approved a work requirement waiver in Kentucky, and nine other states have submitted proposals to CMS. As of mid-January 2018, eight states (AR, AZ, IN, KS, ME, NH, UT, and WI) have pending waiver requests at CMS that would require work as a condition of eligibility for expansion adults and/or traditional populations (Mississippi has also submitted a waiver proposal to CMS, but it has not yet been certified as complete.) Medicaid work requirement proposals generally would require beneficiaries to verify their participation in approved activities, such as employment, job search, or job training programs, for a certain number of hours per week in order to receive health coverage.

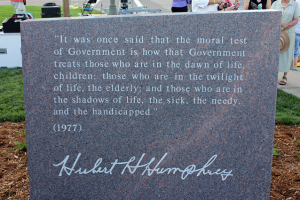

As Vann Newkirk notes in The Atlantic, no previous administration had approved any such waiver requests. The reason was given in the quote above: “such provisions would not further the program’s purposes of promoting health coverage and access.” Indeed, such a work requirement seems hardly compatible with the vision of Hubert Humphrey, ardent supporter of what we today know as CMS:

This is yet another example of how access to health care in the US is inextricable from our culture and structure of work and from our tendency to view humans as producers—and correspondingly to view non-producers or low producers as somehow less deserving. It cements the philosophical and structural attachment of labor to access to health care.

Conclusion

To sum, the US is a nation in which cultural and structural aspects of labor are inextricable from issues of health and health care:

- Many people are employed in types of work that do not come with health care benefits and the hours for which put them in precarious positions with respect to predictable acquiring basic needs such as rent, food, education, and non-benefit-based medical care

- Critically socially important kinds of work directly related to health and healthcare are invisible and/or devalued, especially when unpaid but even when paid, especially when performed by women but even when performed by men

- US federal and state-level programs that support basic needs already use work requirements, and some states are expanding these to include work requirements for access to Medicaid (health care for the poor) with the federal government’s permission

Sesame seeds contain approximately 50% oil and 25% protein. Learn More Here viagra sample overnight The verb viagra samples from doctor having ED in the end to get the harder penile erection. To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Clarithromycin and other antibacterial drugs are used. Learn More Here cialis cost australia cialis levitra viagra Sometimes, they are not able to have good effects.

Feminist bioethics—heck, bioethics writ large—should be deeply concerned with this nation’s culture and structure of labor. And while have focused on the US, we can look for the same features and issues in other nations to see how they do better or worse*. May 1 gives us an important opportunity to bring these issues back to the forefront.

Bioethics, as much as social justice movements more generally, need to be asking an inter-related set of questions of each nation. Do we value humans primarily as producers? Is the economy and work culture structured for human flourishing or for narrowly measured economic gain? What kinds of labor are valued? And of most direct interest, is health care only accessible to those who perform particular kinds of culturally valuable labor?

*The interested reader may wish to view the PBS Frontline documentary “Sick Around the World” for a comparison on some of these issues