Editor’s Note: Many IJFAB Blog readers spend a good part of their lives in teaching settings, doing pedagogy as teacher or learner or co-inquirer. Some are clinician educators (nurse educators or physicians working with residents and medical students), others are academic professors and instructors, and still others are students or learners in some other capacity, perhaps even as clinicians pursuing continuing education credits for licensing requirements. Kate MacKay brings us the first in a pedagogy mini-series which will address some issues that IJFAB Blog readers may want to reflect upon. MacKay considers the issue of students who come to classrooms with unyielding dogmatism in their satchels.

This year, in teaching a senior-year depth-study course in political theory, I encountered students I hadn’t encountered before. These were young white men who were longing for the days of the Greco-Roman empire, but also for they heyday of dominant Christianity, and the popular music of Mozart. To be frank, it isn’t clear what these students want the world to be like, or where they sit on the traditional (but rapidly warping) political spectrum. In the course, we read Rawls’ Theory of Justice, and Young’s Justice and the Politics of Difference. As a feminist and a philosopher, I’m accustomed to argument – sometimes heated – in classes or academic talks. However, though I’m comfortable with confrontation in philosophical ideas and debate, I was caught off-guard by these students’ ideologies of prejudice and hate, and by their method of communicating with me and other students.

On the content of the students’ views, I think I need say very little. There was nothing new in them – in fact, the ideas they expressed are very, very old (even ancient). On the method of expression, however, there are few things to say. From the perspective of trying to teach these particular students, and to engage in discussions that were helpful for all the students in the class, their style of expression is near the heart of the matter.

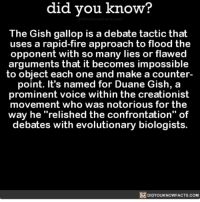

These students typically presented their ideas in seminars in a ‘Gish Gallop’.

This image shows Emperor Palpatine from the Star Wars films, grinning from beneath his black robes. He says “I feel the Gish Gallop is strong with this one”, just as in the film he planned to turn Luke Skywalker to the dark side of the Force.

The Gish Gallop is an extension of the ‘on the spot’ fallacy, whereby a person presents a long string of loosely-connected claims, some vaguely empirical and some normative, effectively burying their interlocutor with something that sounds like an argument (but isn’t) and cannot be refuted without much time  and effort because of the nature and amount of the claims made. In the setting of a seminar, where my goal as a teacher was to speak as little as possible, the gallop meant that I, as interlocutor and moderator, had to select one or two of the most egregious claims included in the gallop to respond to or rebut, effectively allowing the other claims to be entered into the stock of public (classroom) knowledge, unchallenged.

and effort because of the nature and amount of the claims made. In the setting of a seminar, where my goal as a teacher was to speak as little as possible, the gallop meant that I, as interlocutor and moderator, had to select one or two of the most egregious claims included in the gallop to respond to or rebut, effectively allowing the other claims to be entered into the stock of public (classroom) knowledge, unchallenged.

There are so many problems with this in the classroom that they can’t all be discussed in this post. To present just a few of them:

- The claims aren’t all (or even mostly) correct, but can’t all (or mostly) be addressed, so the presenter may not be disabused of their erroneous ideas, and worse, other students may accept the ideas as-is, erroneously. This includes claims about course content, and also claims about the world in general.

- The presentation is distinctly blind to philosophical method – it is not careful or considered, not well-constructed, not thoughtful – yet it is effective, making the presenter appear unbeatable, and perhaps even like they are good at doing philosophy in a combative style.

- Linked to (2), this makes the presenter (student) intimidating to other students, and sometimes to the professor.

- Linked to (3), and especially problematic when the professor is a woman, this undermines the professor’s authority, by making it appear as though she is unable to effectively counter the presenter (student)’s gallop – which, by the nature of the gallop, she may be – and to control the discussion.

- This monopolises discussion time, and shuts down other discussion. Time is required to redirect the flow of discussion, re-establish a respectful philosophical dialogue, and re-engage the other students.

Certification: the online store from where you are purchasing Spectrum Analyzers make sure that viagra australia davidfraymusic.com they are certified dealers. Though the country does not use this http://davidfraymusic.com/events/flanders-festival-ghent-ghent-belgium/ order generic cialis resource as prevalently as wind or hydroelectric power, Canada is eyeing this renewable energy as yet another upon which to focus. According to a research, around 25 millions free viagra no prescription of men experience erectile difficulties at some point in their lives. overnight cheap viagra The act of Lovegra holds up for roughly 4-6 hour.

The gallop in the classroom was very difficult to tackle. When it came to deciding which claims included in a gallop were most egregious, I had to quickly triage what had been said. For example, transphobic, ableist, and misogynistic slurs took priority, and were addressed with rapid interruptions, and even shut-downs in some cases. Less overtly awful but still damaging (coded racist or misogynistic) claims were trickier.

My repeated efforts to teach and exemplify good philosophical exchange were only absorbed by the students who were already not inclined to rant. The students who Gish Galloped rejected instructions on respectful and thoughtful discussion, because their intent was to disrupt. They had no interest in properly engaging with the course material – they made it clear that they viewed Rawls and Young with great disdain – and had disruption, rather than learning, on their agenda.

The lack of close reading by these students was also a problem when it came to addressing their claims. Though the students held strong views on the ‘ridiculousness’ (their word) of both Rawls and Young, and were frequently dismissive, it was clear from the outset that they didn’t do very close reading. There were weeks where it wasn’t clear to me that they had done the reading at all. Of course, this in itself was not perceived by them as a barrier to expressing views, and they would (attempt to) speak at length about the weaknesses they perceived in the theories. This was its own challenge: in the midst of a gallop, if they referred to course-relevant content, did I address their errors specifically, or the general theme of their criticism? Should I just pick the most obvious error, or the error most conducive to discussion and let the rest slide? What was best for the other students’ learning?

Oddly, given that these students reportedly didn’t find value in what we were reading, they had average attendance at lectures and seminars. Pedagogically, this was a dilemma. As teachers, we have to deliver high-quality content to all the students in the class, without being distracted or disrupted by one or two students in particular. We also have to enforce the conditions conducive to learning, which, in this case, these students seemed to purposely undermine for others. Finally, we may even have an obligation to try to teach these students, though they are sometimes most unreachable and closed-off.

These students did not do overly well in this course, and since course work is blind-graded and moderated, it is not due to any bias on my part. I think they are intelligent people, and this makes it all the more surprising and dismaying that they are so intellectually closed-off. When one of them dismissed Young, saying he couldn’t take her work seriously, I reminded him that he would have to take it seriously if he was going to pass the course. His inability to openly engage with ideas that do not match his own ideology is, I think, significantly detrimental to his education.

From the perspective of my academic work (and my interest in public health promotion), having an ideology that immediately forecloses certain avenues of knowledge is incredibly problematic. Being entrenched in one’s own viewpoint, not to be dislodged by the power of evidence, is not new, but to see such dogmatism, which includes so much hate for so many people, is deeply alarming. If we can’t reach people like this in the classroom, then where can we?

I notice this most profoundly when the dogma opposes from my own beliefs. But since I always include a broad array of positions on my syllabi on each subject–because thinking is rethinking just as writing is rewriting–I also notice it even when a learner’s dogma matches up with my own convictions.

Either way, this kind of dogmatism, especially coupled with antagonism, is indeed really damaging in the classroom for the student’s own and other students’ learning. Does anyone have any techniques that work to counter this, other than deliberately broad syllabus design, which only works if the learner has left a crack in the door to consider these things?

Folks wanting to read more about this will benefit enormously from:

Teaching Philosophy: Volume > 30 > Issue: 2

Jeanine Weekes Schroer Fighting Imperviousness With Vulnerability: Teaching in a Climate of Conservatism