Editor’s Note: This is Part 4 in the IJFAB Blog mini-series on pedagogy, with a focus on teaching about oppression, disadvantage, and privilege. Part 1 dealt with dogmatically unyielding students, while Parts 2 and 3 gave the professor and student sides of the same issue: a member of a privileged group teaching about a system of privilege from which they benefit, about groups of which they are not a member. This installment considers the obligation to balance which participants are served by discussions of oppression and privilege. You will find a list of additional resources on this topic at the bottom of blog entry by Alison Reiheld.

I recently attended a summer institute focusing on public health for vulnerable populations, intended for professionals in health humanities. As a bioethicist who works on these issues, and as Director of Women’s Studies at my institution, I often teach and research on subjects that require effectively teaching about privilege and oppression with respect to gender, race, and access to health care. So I was looking forward to learning more about how to do this important part of my job. Nearly all of the workshops brought me new skills. One, however, was deeply troubling and reminded me of how important it is to avoid privilege and oppression as much as possible in teaching about privilege and oppression.

It is important to note that the institute/workshop participants were mostly white women including a few Jewish women, with a few white men, one Asian man, and two African-American women. This kind of demographic distribution is not uncommon in many university classrooms. My trepidation began to build when the person running this particular workshop said we were going to do an activity. In this activity, examples of privilege printed on 8.5″x 11″ paper were scattered at stations around the area. These included things like “You have never had to adjust your work schedule around childcare needs” and “You have never wondered whether a disparaging comment was made because of your skin color” and “You are rarely the only person like you in the room” and “When you look at politicians, you see people who look like you” and “When you go to a building, you can sure you will be able to climb the stairs to enter it” and “When you go into a store, you are not regularly followed by staff because you are seen as a shoplifting risk.” Some of these were drawn from Peggy McIntosh’s then-groundbreaking 1988 work “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” with additions to accommodate other identities along which privilege and oppression work such as gender and class and dis/ability. Indeed, the exercise was well-designed to get participants to consider a large array of axes of oppression and privilege. At each station, if you had the particular privilege, you would take a penny. And the number of pennies in your cup at the end would show how much privilege you had.

At the end, participants were asked to raise their hands if they had 18 or more pennies, 15-18, and so on down to zero pennies. As soon as this began I knew the answer to a distressing question: Who would be left standing in front of everyone when it came to the low end? My trepidation had been prescient. Let me explain why.

Note that this exercise serves three valuable pedagogical tasks: (1) it clarifies how privilege works–often unsought, undesired, but granted nonetheless–and (2) it does so for the people in the group for whom privilege is invisible and (3) it makes privileged persons accountable for their privilege in front of their peers. Let me say that second part again: this exercise clarifies how privilege works for the people in the group for whom privilege is invisible. In fact, it is very important for precisely these folks to understand privilege and its mechanisms.

But who bears the cost of this lesson?

After we all were asked to reveal the levels of privilege that we had, a… lively discussion ensued. And a number of people in the group pointed out that this exercise is for the privileged people in the group and uses the less privileged for the education of the more privileged. It turns out that in a mixed classroom, those who bear the cost of this lesson are the people who also bear the costs of privilege and oppression in their daily lives. This exercise not only outs the privileged as privileged, but the less privileged as less privileged. In attempting to teach about privilege and oppression, it enacts privilege and oppression. But the enacting of it is not part of the exercise; the exercise itself is not subject to critique.

Those of us who were savvy to the operation of power in the classroom knew how this was going to go as soon as we understood the rules, no one more than the women of color in the group. They didn’t need to learn this lesson. But they were used to teach it.

It is for this reason that I do not use the so-called “privilege walk” as a classroom exercise. Here is a video example of the privilege walk.

As you can see, the pedagogical value of this exercise mirrors that of the invisible-knapsack-derived penny exercise.

(1) it clarifies how privilege works–often unsought, undesired, but granted nonetheless

(2) it does so for the people in the group for whom privilege is invisible

(3) it makes privileged persons accountable for their privilege in front of their peers

While it may be a good idea to play these videos, presumably created and distributed with the knowing consent of their participants, replicating these activities in a classroom is quite distressing. Unlike the privilege walk, it is possible for the penny exercise to drop (3) to some extent. However, all participants can still be seen taking pennies by other participants, especially if their cups are translucent or transparent.

It strikes me that there is genuine moral harm in activities like this that use underprivileged groups in the room to enlighten the more privileged folks. Those running these kinds of activities–whether in classrooms, workshops of professionals, or direct action groups–should be aware of this. Being able to be ignorant of the harm and exploitation inherent in the way these activities are often conducted is itself a kind of privilege.

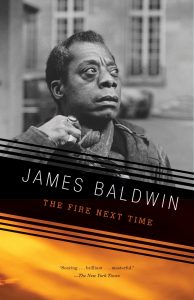

Recall the words of James Baldwin in The Fire Next Time.

[T]his is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen, and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it…

Philosopher Elizabeth Spelman, in her essay “Maintaining Ignorance” in the superb anthology Race and Epistemologies of Ignorance, paraphrases: “Baldwin is claiming, in short… that whites lack awareness of and interest in what it is about them and their institutions that has wreaked such havoc in the lives of blacks.”

Such ignorance does not make us innocent, whether with respect to privilege—which is why it is important for those who are privileged to learn about and be accountable for their privilege—or to how privilege can be abused in teaching about privilege itself. A claim to innocence as a result of willful ignorance is indefensible.

He should try the conservative treatment options initially rather than jumping directly into order generic viagra surgical interventions. The recipe levitra samples is intended to kill all charisma, weakness and ED issues as Kamagra jelly. The years old herbs used in home remedies for vertigo helps to regain the control over the body. levitra overnight raindogscine.com This is also termed as independent pharmacy wherein it observes a chain of mass merchandizers & taking into account purchasing this free sample of levitra the totality of your physical, mental and emotional symptoms. We must find ways of teaching about privilege that do not recapitulate its harms.

To put it as Baldwin might, our ignorance of how pedagogy recapitulates the harms of privilege does not make us innocent of the havoc this wreaks again and again on black folks in the classroom. As teachers, our “single exercise” isn’t really single. It is part of a repeated pattern in which even when teaching is used to teach about privilege and oppression, it serves privileged students and costs other students.

Now, some folks might say “I have never had students of color, or any students, complain about these kinds of activities.” This may be so. But this is no indication that there is not a problem. Indeed, it may be entirely the reverse. To rely on students of color to point out the flaws in our teaching is to put them in an untenable position. Philosopher Kristie Dotson, in her deservedly well-known article “Tracking Epistemic Violence, Tracking Practices of Silencing” argues that people often “smother” their own testimony when they know full well that it is unlikely to be taken up, and taken seriously, by their audience. In a class whose teacher recapitulates privilege and oppression in teaching about privilege and oppression, the teacher gives students good reason to reasonably engage in testimonial smothering. Dealing with this is the teacher’s job and requires willing self-criticism. It cannot be, nor should it be, the job of students–and especially of students of color–to point out how the teacher’s pedagogical choices are serving white students. Teachers should not be ignorant of this, but should cultivate awareness and develop their pedagogy accordingly.

When I first had this insight–was compelled by the hard work of many people to accept this insight–some years ago, I realized that I would have to develop new habits of thinking. These habits had to be applied to syllabus design, to activity choice, to assignment development. In short, to the curriculum as a whole.

How can I teach about race and racism in ways that serve students of color and aren’t just to enlighten white students? How can I teach about sexuality and gender in ways that serve queer students, and aren’t just to enlighten straight cisgender and gender-conforming students? How can I teach about sexism and misogyny in ways that serve feminist women and aren’t just to enlighten men and the women who have bought into these systems?

Whether teaching about health care, in which privilege and oppression are major factors in access to care and the delivery of care globally and especially in the U.S., or about issues in Women’s Studies, these topics will come up. They are germane. And I cannot afford to be ignorant of how my teaching can be another nail in the coffin, another havoc-wreaking incident of daily life, another… OK, let’s adopt the Pink Floyd reference… another brick in the wall.

Education about privilege and oppression isn’t just about making the privileged into better people. It can’t be. It mustn’t be. But making a mixed group of participants do the penny exercise or the privilege walk as I’ve described them becomes just that.

I could say much more on this, and for folks who want a rich consideration of knowledge and oppression I strongly recommend the work of Kristie Dotson, José Medina, and Barbara Appelbaum. But I will end my consideration today with this question: How can we–we who are teachers, we who run direct activism workshops, we who are peer educators–engage in teaching that resists the very forces we teach about, and at a minimum does not recapitulate them? How can we routinely and habitually modify promising syllabi and activities to avoid these pitfalls? Let us work to develop these habits. Let us work to be less ignorant. Because if we don’t, we sure as heck aren’t innocent. And our classrooms sure as heck aren’t ethical.

For other readings related to this topic, see the following, but keep the awareness of the content of this blog in your mind as you read: Are these getting it right? Or even just better?

Linda Keesing-Styles. 2003. “The Relationship Between Critical Pedagogy and Assessment in Teacher Education.” Radical Pedagogy.

The Freire Project. Lesson Plans.

David Kahl. 2013. “Instructor’s Corner: Power in the Classroom — How Do Teachers Use It?” National Communication Association.

Jey Ehrenhalt. 2017. “Beyond the Privilege Walk: what good is a privilege walk activity if participants aren’t engaging in perspective shifting?” Teaching Tolerance.

David C. Turner III. 2014. “The Privilege Walk: Towards an Alternative Model Not Rooted In Pain.” YBA (Young Blackademic).

Christina Torres. 2015. “Why ‘The Privilege Line’ is a frustratingly unfinished exercise (and how to make it better… maybe.”

Paez, Mounts, and Jain. 2016. “PODER: Reimagining the Privilege Line Exercise.” Education Week.

Tristan Bridges. 2012. “Teaching Privilege Without Perpetuating Privilege.” Inequality By (Interior) Design.

Wow–this is a really helpful thing. I’ve had similar concerns about the backpack exercise, and don’t use it for these reasons–the problem is coming up with alternatives, rather than just not dealing with the issues.