EDITOR’S NOTE: This contribution comes to us from new contributor Sean Valles, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Michigan State University. Valles studies the interplay of ethics and scientific evidence in population health, including race & migration issues and climate change issues.

“Help, bioethics friends. The bioethics blog I run is all bad news. Do we have ANY good news?” Alison Reiheld posted that question on social media, leading to a conversation and now this blog post. So, to answer her question, I see the growth of the interdisciplinary field “population health science” as good news. This is the field I examine in my book, Philosophy of Population Health: Philosophy for a New Public Health Era (Routledge 2018). I was motivated to make sense of how and why scholars writing about “population health” created a scientific framework that has “an explicit concern with health equity” as a foundational tenet (Diez Roux, 2016, p. 619).

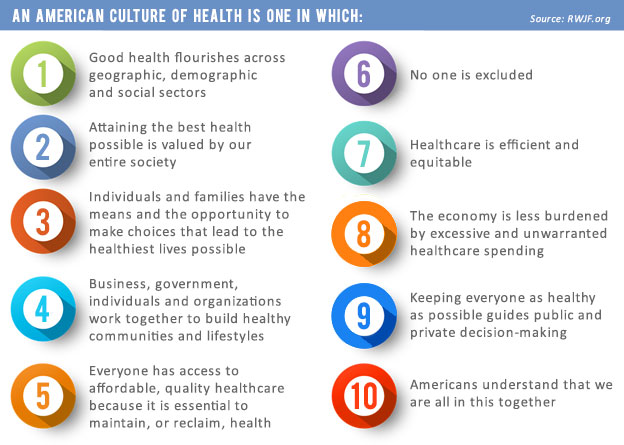

The field has a professional society, introductory volumes (Keyes & Galea, 2016) and textbooks (Nash et al., 2016), etc. It also overlaps in complex and disputed ways with contemporary public health science, such that it is hard to tell where “public health” ends and “population health” begins (Diez Roux, 2016). The best-known population health catchphrase is “culture of health,” popularized by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

So why is the growth of this field good news? More reasons than I can summarize here, but most of all because it is a field/approach/framework that approaches health as a phenomenon enmeshed in the diversity, messiness, and injustices of everyday social life. That orientation, and a commitment to ameliorating health injustices, has led population health to endorse positions long endorsed by feminist philosophers.

Even just the notion of aiming for a “culture of health” is a welcome change of pace for me as a feminist bioethicist. Gendered health inequities often manifest clearly in the clinic—eating disorders, discounting of women’s accounts of their pain, pathologizing of bodies and behaviors that don’t conform to binary gender norms, etc.—but the roots of those inequities are in culture and everyday life.

As I review in Chapter 2, population health science is built from a gradual recognition—largely over the course of the second half of the 20th century—that health is fundamentally social in several senses.

1) The World Health Organization stated during its founding after World War Two that health is the presence of well-being in social context (I defend a modified version of this view in Chapter 3).

2) In the following decades, alarming data emerged showing that social structures (social determinants of health) have massive power over even things that can appear to be individual choices—I choose my diet in roughly the same limited sense that I choose which language I speak at home.

3) Effectively promoting health effectively requires a social ethics rooted in empowerment. As the 1986 WHO Ottawa Charter, which heavily influenced the field, puts it: “Health is created and lived by people within the settings of their everyday life; where they learn, work, play and love. Health is created by caring for oneself and others, by being able to take decisions and have control over one’s life circumstances, and by ensuring that the society one lives in creates conditions that allow the attainment of health by all its members.” (World Health Organization, 1986)

4) Health is methodologically social in the sense that we need to develop better participatory methods to responsibly elicit and synthesize health knowledge from patients, community activists, social scientists, physicians, nurses, etc.

Every one of these social understandings of health is a welcome departure from the elements of public health that many bioethicists—especially feminist bioethicists—have long opposed: paternalism, cultural imperialism, inattention to social structures and power dynamics that serve to create inequitable privileges, and more. As reviewed in a new 2019 IJFAB paper by Julia Gibson, “So much outstanding [feminist] scholarship has been devoted to championing sociality (Jaggar 1983; Lindemann 2014), relationality (Anzaldua 1990; Plumwood 2002; Haraway 2008), and community (Weiss and Friedman 1995, Kimmerer 2013) in the face of liberal individualism—amongst other oppressive ideologies—run amok” (Gibson, 2019, p. 77).

The thing that makes me most sanguine about population health science, and a feature that makes it good news for feminist bioethics, is its commitment to epistemic humility. The final chapter of my book surmises that population health science has tacitly but clearly embraced a commitment to three related forms of humility:

1) A general epistemic humility

2) Intersectoral humility: government, non-profits, the healthcare industry, and other sectors each have roles to play in health promotion, but none deserves a hierarchical position above the others

3) Interdisciplinary humility: health has many facets and no single discipline sees all of the facets

In that section, I rely on Anita Ho’s excellent IJFAB article explaining the relationship between epistemic humility and collaboration: “[epistemic humility] means a commitment to make realistic assessment of what one knows and does not know, and to restrict one’s confidence and claims to knowledge only to what one actually knows about his/her specialized domain. In particular, it is a recognition that knowledge creation is an interdependent and collaborative activity” (Ho, 2011, p. 117).

Population health science is built on a sense of humble awe about the vastness of health as a social phenomenon, an orientation that will help us confront the socially complex challenges facing public health. We’ve invented effective biomedical tests and treatments for HIV disease, but haven’t figured out how to make them safely accessible to all (see Chapter 6). We’ve found it’s easier to talk about the Dakota Access Pipeline as a source of toxic risks from oil spills than it is to listen to Standing Rock Sioux accounts of how badly the pipeline harms a community wherein the well-being of land, water, and humans are philosophically tightly linked—where “water is life” (see Chapter 2).

The world is very very far from being a place of equitable thriving for all. Unchecked climate change looms over all good news, and population health gains are uneven. Most countries in the world have rising life expectancy, but that is cold comfort to Americans who are in the midst of a rare and frightening three-year-long (possibly four if the trend holds) downturn in life expectancy, a trend not seen since the four-year period that included World War I and a global flu pandemic.

Even when the days are dark, I think it is worth celebrating when one finds good allies to face them with.

References

Diez Roux, A. V. (2016). On the Distinction—or Lack of Distinction—Between Population Health and Public Health. American Journal of Public Health, 106(4), 619-620.

Gibson, J. D. (2019). The voices missing from the autonomy discourse (are also the most indispensable). International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 12(1), 77-98.

Ho, A. (2011). Trusting experts and epistemic humility in disability. International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 4(2), 102-123.

Keyes, K. M., & Galea, S. (2016). Population Health Science. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nash, D. B., Fabius, R. J., Skoufalos, A., Clarke, J. L., & Horowitz, M. R. (Eds.). (2016). Population Health: Creating a Culture of Wellness (Second ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Valles, S. A. (2018). Philosophy of Population Health: Philosophy for a New Public Health Era. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

World Health Organization. (1986). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Retrieved from Ottawa, ON: https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/