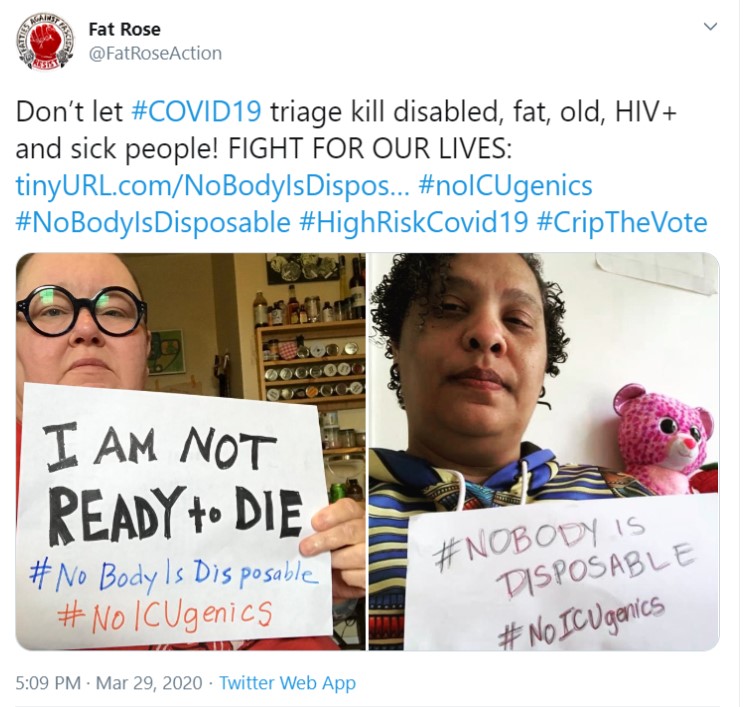

The coronavirus pandemic has sparked new fears among fat activists that fat people will be sacrificed in virtue of medical triage protocols used to ration ventilators, ICU beds, and medicine, which are all in critical supply throughout America (hereafter I focus on mechanical ventilation and other methods of oxygenation including extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, although the conclusions broadly apply). An April article from Bitch Media reports that the Twitter hashtags #NoBodyIsDisposable and #NoICUgenics began trending after a Washington state neurologist posted a now-deleted tweet saying that “Seattle has 12 machines, which is less than what’s needed. So a central committee there is deciding: You can’t go on [ECMO machine] if you’re [over] 40 years old, if you have another organ system failing, or…incredibly…if your [body mass index] is [over] 25. Turns out these are all major poor prognostic signs.” People organizing around the Twitter hashtags eventually developed a media and letter-writing campaign urging care providers to “refuse discriminatory triage policies” that target marginalized groups, including the fat, elderly, disabled, and those with AIDS.

But are hospitals and healthcare providers sacrificing fat people to save others via triage protocols? And regardless of whether they are, should they? (Spoiler: the answers are maybe, and no, respectively).

Do triage policies explicitly discriminate against fat people?

The answer ranges from “maybe” to “probably not”.

There is a lack of evidence that hospital triage policies are explicitly discriminating against people based on body size (in Washington state or elsewhere), but the fear that one will be denied a hospital bed, a life-saving treatment, or a medical device like a ventilator on the basis of size is nevertheless well-founded. Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) prohibits discrimination “on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability” among most health care providers, and the Department of Health and Human Services has intervened recently against discriminatory ventilator triage protocols. However, body size is not explicitly mentioned as a protected class in the ACA, and whether body size counts as protected under another category (like disability) is legally murky at best. So, we have reasons to think that discriminating against fat people in triage policies is legal at the federal level.

Do triage policies implicitly discriminate against fat people?

The answer to this question is more complicated and ranges from “maybe” to “probably yes”.

According to a recent study which analyzed triage policies from 29 different hospitals in 18 states and the District of Columbia, the most commonly mentioned triage criterion is benefit (mentioned by 25 policies, or 96.2%). What is benefit in the context of a triage policy? Triage policies based on benefit evaluate who is least likely to benefit from mechanical ventilation and exclude them from receiving the treatment, or the policies evaluate who is most likely to benefit from ventilation as measured by increases in survival. In other words, a strategy of maximizing benefits aims to either save the most lives or save the most life-years. How is benefit determined? In the study, about four out of five hospitals employing benefit in triage decisions used a scoring system like the Sequential Organ Failure System (or SOFA, which calculates risk of death based on organ performance), while some policies also restricted resource allocation based on specific diagnoses like cardiac arrest. Furthermore, the study does not mention that any policy reviewed excluded body size from factoring into resource allocation decisions.

Although a study including 29 policies is not necessarily representative of triage policies across the country, this study is the most recent attempt at comprehensively analyzing triage policies in hospitals and other care settings, so we can reasonably use it to draw out some general implications. If a triage decision policy uses a scoring system like SOFA, that policy may systematically mis-rate those with a higher BMI. For example, SOFA scoring relies on measuring a deviation from baseline levels of biological factors like white blood cells, creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen. However, at least one study has shown that individuals with a higher BMI may have higher deviations from the baseline than individuals with a lower BMI, raising the possibility that SOFA may be an “inaccurate representation of actual severity of illness or organ dysfunction” among individuals with a higher BMI.

The problem generalizes to other scoring systems. QALYs are quality-adjusted life years, a measure combining the expected length and quality of life gained from a medical intervention. Multiple studies cite obesity as a factor reducing the QALYs gained from medical interventions. However, “obesity” is defined using BMI, which doesn’t account for variations at the individual level in terms of comorbid conditions and other measures of health. At 259 pounds and 6’5″ tall, Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson is classified as obese because he has a BMI of over 30, but The Rock is clearly not fat nor does his BMI tell us anything else about his overall health. Even among fat people with high BMIs, there are hugely varying degrees of metabolic health and physical fitness. Lizzo regularly performs incredible acts of stamina by singing and dancing at live shows for hours in spite of getting body shamed by people like celebrity trainer Jillian Michaels.

In short, although we do not have definitive evidence that triage scoring systems discriminate against fat people, it is well-documented that these scoring systems discriminate according to traits like disability status or age. And as we have seen above, it is well within the realm of possibility that these systems discriminate against fat people as well.

Moreover, in triage protocols that allocate resources according to benefit, fat people are probably even worse off if the protocol is based on a doctor’s subjective judgment, rather than a scoring system. Doctors are fatphobic. A survey of physicians in 2003 found that over half of respondents viewed “obese” patients as “awkward, unattractive, ugly, and noncompliant”. These attitudes reduce the quality of care that physicians provide to fat people and can worsen their health outcomes.

In determining who would benefit the most from a treatment, is a doctor going to choose a fat person over a non-fat person? It seems unlikely to me. In addition to the fatphobic attitudes and implicit bias doctors have against fat people, the New York Times has recently reported that obesity is linked to hospitalization and poor health outcomes among coronavirus patients. Even the CDC claims that severe obesity, which they define as having a BMI of 40 or greater, increases one’s risk for coronavirus complications. Perceptions of fat people as more adversely affected by coronavirus may make doctors think that fat people are more susceptible to the virus and less likely to survive. Doctors may in turn think allocating resources to fat people is a worse strategic choice if one wants to maximize the number of lives saved.

Should triage policies discriminate against fat people?

No.

Firstly, it’s not clear that fat people who get coronavirus are necessarily worse-off than non-fat people. What may be true is that fat people are more likely to have certain pre-existing health conditions that can worsen the effects of the coronavirus. The New York Times article above hypothesizes that fat people may have “compromised respiratory function” and “an increase in circulating, pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may play a role in the worst Covid-19 outcomes”. And it’s true that fatness can lead to decreased tidal lung volume and an increase in chronic inflammation and inflammatory cytokines. But those metabolic and physical features are not caused by being merely fat. They’re caused by being fat and sedentary! Regular exercise or physical activity is associated with both greater tidal lung volume and less chronic inflammation and cytokine response. I’m willing to bet that fat ultra-marathoner Mirna Valerio has way better respiratory function than your average sedentary thin person.

The point is coronavirus probably does not cause worse health outcomes in fat people only because they are fat. Furthermore, some of the challenges of treating fat patients generalize to all large patients. Larger bodies are harder to provide care for: they are harder to move and maintain while unconscious and can be harder to oxygenate (thanks editor Alison for this point!). People on ventilators are often put into a medically-induced coma. But it is just as hard to move and care for a fat person in a medically-induced coma as it would be to care for a comatose Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson. In short, it may be true that fat people suffer worse health outcomes when they get coronavirus. But that’s not merely because they are fat. So, using fatness as a metric by which to calculate treatment benefits in triage scenarios is a bad practice. A doctor cannot tell how someone is going to react to a ventilator just because the doctor sees that the person has a larger body.

Secondly, even if fat people have worse health outcomes generally from coronavirus, that still does not make denying fat people medical resources a just triage practice. I have argued elsewhere that fat people are oppressed. Size ought to be a federally-protected class, the same as race and disability status. As the disability rights activist Ari Ne’eman said, “By permitting clinicians to discriminate against those who require more resources, perhaps more lives would be saved. But the ranks of the survivors would look very different, biased toward those who lacked disabilities before the pandemic. Equity would have been sacrificed in the name of efficiency.” Although Ne’eman was referring to physicians discriminating against people with disabilities, his statement applies to fat people too. Why should we sacrifice fat people to save others just because they are fat?

One reason you might think we should do so is because fat people are morally responsible for their fatness. You might say, it’s their fault they’re fat! Fat people do worse with coronavirus. Free up beds and ventilators for skinny people who deserve them. But we’ve already shown that doctors using fatness as a rule of thumb for who will perform poorly on a ventilator are going to judge incorrectly sometimes. And being fat is not a personal decision, nor is it something that is usually within one’s control over the long-term (and although I lack the space to defend this claim fully here, I argue for it at length in my own piece linked above). Although people can lose weight in the short-term, they tend to gain it back over the long term, and fluctuating weight via yo-yo dieting comes at a great metabolic cost to one’s body. We don’t hold people morally accountable for things outside of their control (in most everyday circumstances). We shouldn’t hold fat people to account for their body size either.

So how can we fix triage policies to be more just for fat people?

I think that Savin’s and Guidry-Grimes’s suggestions for minimalizing ableism in triage protocols apply equally well for fat people. In particular:

- make proposals for triage protocols available and accessible for community comment

- involve the fat community in crisis planning

- avoid triage exclusion criteria that refers to body size, and

- limit the information that reaches the triage team or officer to information that is medically relevant, including weight, BMI, and body size.

The last point is important. Doctors can describe lung function without referring to body weight or size. Unless it is medically relevant, those attributes should not be included in information that is used by the triage team or officer. Not including information about body size or weight reduces the chance of decisions being clouded by implicit bias.