Like many medical professionals, when I read this Tweet (above), I was hurt and immediately defensive. We aren’t militarized. We aren’t trying to kill people. We’re here to help people, not hurt them. Sure, there are some bad people who are doctors. But I’m not a bad person, and the vast majority of the people I work with aren’t bad people. This is so unfair!

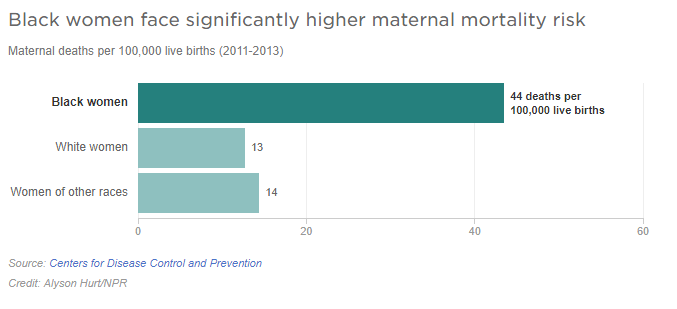

But is it? I suspect it’s true that most police officers pursued that line of work to help people. Most of them are probably not bad people in the traditional sense. Like most of my friends on social media – both conservative and liberal – they no doubt espouse the belief that everyone is equal and should be treated equally. But George Floyd was still murdered. And black people die disproportionately with COVID-19. And black mothers are over three times more likely to die due to pregnancy and childbirth than white women.

The ”goodness” or “badness” of individuals is not the point.

The American experience is one that is inherently racist, and the consequences of that racism play out on American streets and in American hospitals every day. Some of it is the effect of implicit bias. Studies show that doctors are more likely to take the pain of white patients seriously when compared to black patients. Black patients are less likely to receive life-saving interventions for heart attack than white patients. Serena Williams had to diagnose her own pulmonary embolus.

None of these findings are meant to suggest that providers are intentionally providing substandard care to black patients. But a set of unquestioned beliefs underlie the interpretation of information provided by black patients, and those beliefs can alter the approach to care.

If that were the only issue, the answer seems pretty straightforward: if we just make the implicit explicit, if we just educate ourselves, then the disparities should resolve. Incorporate implicit bias training, and all our problems will go away. Unfortunately, implicit bias training alone doesn’t seem to work – and for some may even provide an excuse for racism by absolving them from the responsibility for racist beliefs. And even if it is effective for some – even if we can eliminate bias by calling it out – it still wouldn’t be enough.

Effectively eliminating health disparities requires that we incorporate our patients’ lived realities. In everything but race, we recognize this. We ask about family history, smoking history, education, and employment because we understand that those are risk factors for certain medical conditions. And for those that are modifiable, we work to modify them. We know smoking cessation is hard, and it often takes many attempts before it’s successful. But we ask, and we offer support, and we write Chantix prescriptions because we know it’s important. We recognize that there is a level of personal responsibility, but we also attribute responsibility to cigarette ads that targeted patients as children and to tobacco companies that utilize nicotine to create physical addiction and increase sales. Personal responsibility functions within the context of an individual’s cultural experience.

The same concept applies for patients of color. Educational disparity, generational poverty, and differential access to healthy food options (to name just a few examples) all concretely impact baseline health status. Weathering is also increasingly recognized as an important contributor to health disparities. A full explanation of the concept of weathering is beyond the scope of this commentary, but the general premise is that the constant stress of being black in America creates physical changes that increase the risk for a variety of medical conditions. The cultural experience for our patients of color is different in ways that meaningfully affect health.

Somehow, despite our recognition that we should attempt to intervene to reduce the impact of smoking or on-the-job health risks, the specific lived realities unique to our black patients are not considered to be our responsibility as physicians. If a patient with diabetes doesn’t have good control, we admonish her about dietary choices without exploring whether or not she has access to fresh vegetables near home. If a pregnant patient misses multiple appointments, we label her as “non-compliant” and excuse ourselves from responsibility for poor outcomes without considering the role of transportation, missed work, or childcare in her absences. Recognizing these factors puts additional responsibility on physicians to attempt to address them.

As such, working to address racism in society at large isn’t going “above and beyond” for physicians. If we believe our job is to identify and mitigate factors negatively impacting our patients’ collective health, then fighting racism in society – not just in ourselves or in our hospitals – is part and parcel of the job. Doing so doesn’t absolve patients of agency in their own health. Rather, it removes roadblocks to agency to assist patients in efforts to improve their overall well-being.

We resist the notion that we are hurting patients. We want to blame something else for identified outcomes disparities. We want to blame bad outcomes for black moms on higher rates of diabetes or heart disease. But if we do nothing to address those things that contribute to higher rates of diabetes or heart disease, then we’re no better than the officers that stood by and did nothing for 8 minutes and 46 seconds while George Floyd’s heart stopped.

You don’t have to individually fix it all, but you have to get involved with something outside the walls of your clinic. Volunteer at a school to help address educational disparities. Participate in community boards to address food deserts. Send money to legal support funds for people of color. At the very least – vote like your patients’ lives depend on it. If the last three years have taught us nothing else, it is that our elected officials matter. Choose wisely.

Editor’s Note: previous IJFAB Blog coverage of race and health (women’s and general) for Black Americans includes

- “Health Disparities Highlighted by COVID-19 Also Show Up In Other Conditions: America’s Amputation Crisis“

- “COVID-19 Childbirth Restrictions Could Disproportionately Harm Black and Native Women”

- “Woman’s Body as Public Property: Title X and Reproductive Choice…“

- “Society is too slow to learn what learned people look like: Black women ARE what a doctor looks like“

- “Individualization, Access, and Bias: ACOG issues new consensus call for improvements to maternal health care, but there are serious pitfalls to watch out for“

- “King’s Words on Health Injustice: what did he actually say?”

- “The public health response that drug addiction should always have gotten is coming into play for opioids in a way it never did for crack“

- “Keisha Ray makes an important analysis of black women’s maternal health disparities in the US“

- “Things That Ought Not To Be” (on forced/coerced sterilization)

- “None of us are getting out of here alive. But who goes first, and why? New JAMA article.“

- “Sleep as a matter of justice“

- “Telling Tales: Narratives About Black Men and Obesity” (commentary on police violence and beliefs about black physiology)