Editor’s Note: This post comes to us from Guest Contributors Carina Fourie and Agomoni Ganguli-Mitra. Agomini has previously contributed work for IJFAB Blog on pregnancy as a superhuman feat. Prof. Fourie holds the Benjamin Rabinowitz Chair in Medical Ethics in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Washington. Prof. Ganguli-Mitra is Lecturer and Chancellor’s Fellow in Bioethics and Global Health Ethics, as well as co-Director of the Mason Institute for Medicine, Life Science, and the Law at the University of Edinburgh. This entry was written in late summer 2020; ironically, posting was delayed due to the disproportionate effects of COVID and COVID responses on the Editors of IJFAB Blog, both carrying increased personal and professional responsibilities.

An internet search of ‘gender inequality COVID-19’ can produce what seem to be contradictory results, even within the confines of a single newspaper’s articles. Take The Guardian: “Coronavirus hits men harder” from April 7 and “Coronavirus pandemic exacerbates inequalities for women” from April 11. Similarly, one of us emphasized in an interview, that the effects of the pandemic are more or less severe according to a person’s position in society, including their socio-economic status, or their gender. Due to women’s often subordinate and disadvantaged social positions, the pandemic is hitting them particularly hard. The first comment on the interview raised doubt about these claims, citing for example, the higher mortality rates for men from Covid-19. What are we to make of this? Are men or women worse off in the current pandemic?

An exploration of these questions helps to underline the problem with defining the moral aims of public health planning for pandemics as the protection and promotion of health exclusively, or the reduction of health disparities, or both – at least where ill-health is measured as the morbidity and mortality associated with the pandemic disease. Pandemic planning must take account of the effect of pandemics and responses to them on existing social injustices, and on how health can be affected both by the disease itself as well as by responses to the pandemic.[1]

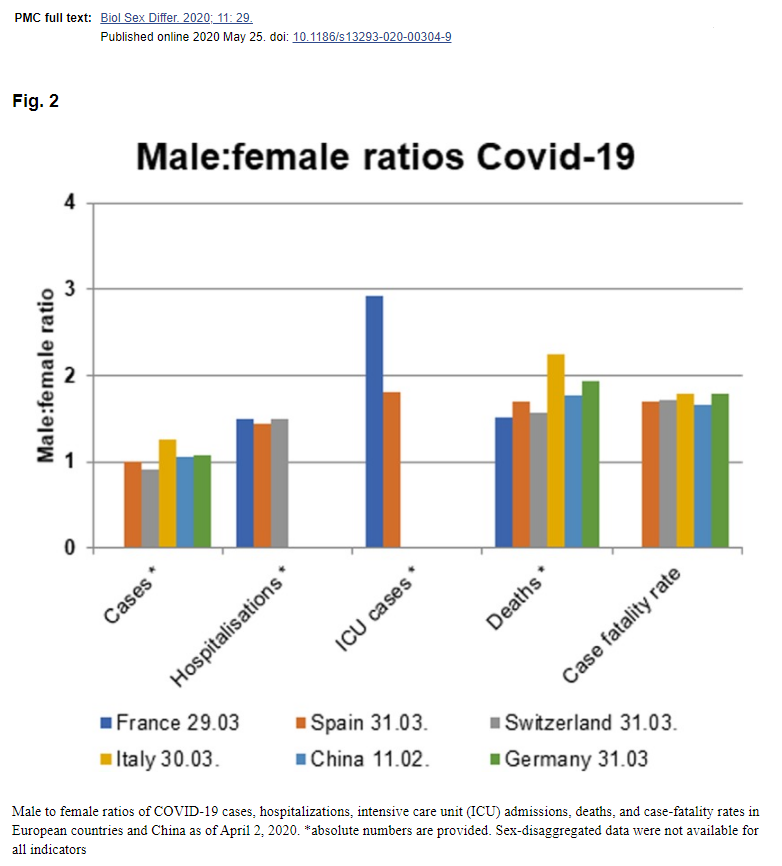

Even a cursory glance at the supposed contradictory claims – indeed, at the subtle difference in the headlines which refer to the impact of the Coronavirus versus the impact of the Coronavirus pandemic – demonstrates that there is no contradiction. Men with COVID-19 are harder hit in terms of worse outcomes and mortality in comparison to women with COVID-19. On the other hand, social inequities and power relationships that disadvantage and marginalize women are exacerbated by the effects of the pandemic: think, for example, of women being more likely to shoulder an unfair burden of caring for children, the ill and the elderly, and the increase in domestic violence during social isolation.

One way of parsing this out is to make a distinction between chromosomal sex and gender. While more research is still needed as to why men are more likely to die due to COVID-19, one hypothesis is that men, or more accurately those persons with XY chromosomes, have less aggressive immune systems than those with XX chromosomes and are thus more susceptible to infections. In contrast, those who live in the world—and within widespread patriarchal structures—as women, are systematically disadvantaged in terms of resources, status and power, and are subject to gendered norms and expectations that exacerbate those disadvantages.

As several countries began to impose lockdown measures as a form of aggressive social distancing, concerns were raised about the lack of access to family planning and safe abortions. The UNFPA has recently suggested that up to 47 million women could lose access to contraception, and that extended lockdowns could lead to 7 million unintended pregnancies. In the US, women’s access to abortion was blocked in a number of states because abortion was categorized as a ‘nonessential’ or ‘selective’ procedure.

Women’s aid organisations raised the alarm over women being confined with their abusers in a situation of quarantine. Within days of the lockdown in the UK, there were reports of an increase by 25% in domestic abuse, which echoed early worries arising from Wuhan and across the world. Concerns are beginning to emerge that women of colour in the UK are less likely to access support for family violence during this time, as they might be more hesitant, or unable to access online support. In the US increases in domestic violence are being reported along with the weaponization of COVID-19, where, for example, perpetrators refuse to allow victims to wash their hands, increasing fear over the possibility of contracting the virus as part of the abuse.

The closure of schools and home isolation across the world have also had specific effects on women, who will have seen their caregiving and emotional burdens heavily increased, with potentially important repercussions for their mental and physical wellbeing, as well as their career advancement. The repercussion will of course be far more severe for women running single-parent households. On the other, more formal end of the caring sector, women are heavily represented within the nursing community, within hospital and in the care sector, with potentially less power and voice than male staff in those contexts. Women make up over 80% of the global nursing and midwifery workforce. Pregnant women who work within the NHS will face additional vulnerabilities, and still continue to work at the frontline.

There are several implications of this for pandemic planning and responses, and for the foundation of public health ethics more broadly. The first is theoretical: concerns about inequity and health should not be reduced merely to concerns about health inequities; we should also be concerned about the impact of social injustice on health, and health on social injustice. A common understanding of public health is that its core ethical aim is to maximize population health, where ill-health is often measured in terms of mortality and morbidity. This has been criticized from a health inequity perspective: we shouldn’t merely be protecting the health of the general population, we should be concerned about reducing unfair health disparities between social groups, (and we should do that even if that sometimes means we are not maximizing the population’s health in the process).

Taking up such a perspective, an improvement on a mere maximizing approach is ethically inadequate for responses to pandemics. Broader social injustices along with their interactions with health, including structural sexism (as well as racism, ableism, classism, and so on), should also inform a pandemic response. The health inequity perspective might lead us to ignore the social injustices that women face during and following a pandemic. This is particularly likely to occur if the measures of health that are used to determine who is doing better and who is doing worse are the mortality and morbidity rates associated with COVID-19 – using these could indicate that women are among the more advantaged. Of course, ironically, not only are women doing badly according to many measures of social justice, the exacerbation of certain social injustices impact health directly, for example, through domestic violence. Furthermore, as health is socially determined, the exacerbated injustices can negatively impact women’s health, although this will not be picked up if our concerns are mainly with the mortality and morbidity associated directly with COVID-19. This is not to say that mortality and morbidity rates are not significant. These rates are and should be taken seriously – but it does become a concern when a reduction in these rates come to entirely represent a successful response to a pandemic.

Second, there are practical implications for data collection, and for developing guidelines for pandemic responses. Sex-disaggregated data are crucial to understanding the differential effects of a pandemic on bodies that are biologically different, but also to the extent that these track the gendered social and structural effects of the pandemic. Additionally, data on race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and disabilities, along with data on other social groups who are marginalized, should also be collected. Evidence arising from various countries suggests the considerable impacts of the pandemic on people of color and minority populations. The collection of data on other disadvantaged social groups is necessarily independent of concerns about gender and sex; however, it is also necessary as part of investigating the compounding of gender with other inequalities that will help to identify the specific needs of women of color, working class women and women with disabilities, for example.

The differential effects of the pandemic on women and on gender inequalities will be important secondary effects of the crisis, and must be an essential part of developing guidelines for pandemic planning and response. Plans specifically designed, for example, for how to detect and respond to domestic violence, and how to support survivors of domestic violence during quarantine and social isolation need to be developed. Recognition of intersectional compounding should take into account that people of color and minority populations are less likely to be have reliable access to online domestic violence support, for example, and thus planning needs to be adapted to ensure that it is not only white women or middle-class women who are supported.

As policy-makers consider various models of public health measures in pandemics, existing social injustice should thus be—systematically and explicitly—considered, and the outcomes of measures taken should be tracked, with particular attention to compounded effects and to the effects of existing gender inequities.

[1] See, for example, Madison Powers and Ruth Faden (2006) on how social justice should be the moral foundation for public health, and Debra De Bruin and colleagues (2012) on the importance of social justice for pandemic planning. Powers, M., Faden, R., 2006. Social Justice: The Moral Foundations of Public Health and Health Policy, 1 edition. ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford. DeBruin, D., Liaschenko, J., Marshall, M.F., 2012. Social Justice in Pandemic Preparedness. Am J Public Health 102, 586–591. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300483