Editor’s Note: Part 3 in our pedagogy mini-series comes to us from Elon University student Arianne Payne, an African-American woman who reflects on taking a course on rap, one which touches on racism and black culture, from a white male professor (that professor authored Part 2 in our series, while a stand-alone piece was Part 1). In particular, she discusses her reservations about this course being taught by a white professor, at all. Ms. Payne is a rising junior at Elon University double majoring in Communication Design and English with a concentration in Creative Writing. Arianne has a passion for art and creativity, which have both been impacted and affected her academic career. As a 2018 recipient of Elon’s Lumen Scholarship, she will begin a two-year creative research project on Native American and African American communities this coming Fall.

“I met this girl when I was three years old, and what I loved most, she had so much soul”

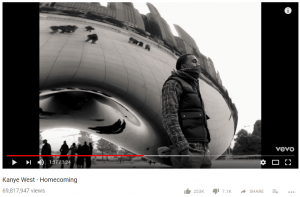

These are the opening lyrics to Kanye West’s “Homecoming”: a song in tribute to Chicago. They pay homage to fellow Chicagoan rapper, Common, who used similar lyrics in “I used to Love H.E.R”. As problematic as Kanye is, which I won’t get into here, these lyrics welcome me back to Chicago on every flight home from college. On every school break, they roll off my tongue as I reconnect with high school friends and the lights of my glowing city. I don’t know when I fell in love with hip hop, but I know these memories are one of the reasons why.

This image shows a screenshot from Kanye West’s “Homecoming.” A man, with face half-covered, stands in profile in front of the iconic “bean” (AKA Cloud Gate by sculptor Anish Kapoor) located in downtown Chicago at Millennium Park. The sculpture is a gigantic mirror-surfaced fluid object shaped roughly like a kidney bean. It reflects the city skyline and its people, including the observer, from any angle except directly below. From underneath the bean, one sees oneself and the people who are also below it.

Hip hop originated in the Bronx, New York City in the 1970’s in a postindustrial urban landscape. Hip Hop Scholar, Tricia Rose, describes hip hop as an “Afro-diasporic cultural form which attempts to negotiate the experiences of marginalization, brutally truncated opportunity and oppression within the cultural imperatives of African-American history” (Rose, 71). Postindustrial conditions, such as the formation of new international divisions of labor and new migration patterns from developing nations, have contributed to the economic and social restructuring of urban America which can still be seen today. In the 70’s cities experienced the loss of federal funds for social services, the displacement of industrial factories, and the conversion of real estate into luxury housing, leaving working-class residents with a diminishing job market, social services, and affordable housing (Rose, 73). Hip hop emerged as a way for black youth and youth of color to create identity and social status in a structurally changing community. Rappers, DJs, break dancers, and graffiti artists were facets of what is now known as hip hop. Artists in these realms not only elevated black youth identity, but also articulated approaches to art that were found in the African diaspora.

In the 80’s hip hop saw a shift from being community and DJ based to being emcee based, which was a result of commercialization as it moved from the Bronx and spread to Manhattan and other major cities across the country. This changed the consumption of rap music to be largely consumed by white audiences, which we still see today. Although historically and artistically hip hop is a black art form, this shift allowed space for white people to engage with and contribute to the evolution of hip hop.

I saw a first-hand example of the ways that white folk can engage with hip hop as I took a class called Rap, Race, Gender, and Philosophy this semester. Unlike most classes that you check off as a requirement, I was truly excited about this one. I have loved hip hop for as long as I can remember. From watching 106 and Park as a child, to listening to my older sister’s mixed cds, the legitimacy of hip hop was never a question in my life. Hip hop music is on the soundtrack of my life, as well as the soundtracks of many other black youth. Learning about it in an academic setting seemed like an experience that would enhance my understanding of the music.

When I walked into class on the first day, I was initially apprehensive. I had heard amazing things about this course, the material, and the professor, but the professor was a straight white man. I didn’t know if this was going to go great or Dear White People bad.

Continue reading →