Oliver Sacks gave the Beatty lecture on the mysteries of the brain at McGill University in Montréal in October of 1997. I had the pleasure of being one of the many attending this exciting lecture. I write “exciting” as Sacks has a special gift for transmitting his love of neurology. In fact, to say that Sacks appreciates neurodiversity would be a gross understatement: he holds it in wonder. In this lecture, he explained that while in residency he was told by his supervisor to visit a patient who had dementia. The chief resident believed that Sacks only needed to spend a few minutes there and that he would be acquainted well enough with dementia. However, as Sacks recounts it, he was fascinated by this patient and the phenomenon of dementia and kept returning to visit with the patient. This struck me; many individuals consider people who have dementia as simply “out of it”. In my encounter with healthcare professionals in nursing homes, it has been the case that they usually consider those with dementia at times annoying, most of the time tolerable but certainly not fascinating. Yet, here was this neurologist, who knew how brains work optimally and who took the time to be in the presence of someone whose brain did not function in a regular way. For Sacks, it is a wonder that some brains have a different take on reality. In Sack’s perception, it does not need to be corrected necessarily; it is simply fascinating. He accepts diversity as one of those facts of life that so interesting. Sacks, in all his writings, and especially in person conveys his unwavering sense of wonder at other brains and other ways of apprehending the world. He truly appreciates diversity. This is a rare gift and luckily for us he also possesses another gift which is the capacity for sharing this sense of amazement. We can all thank him for the rigorous work he had undertaken in neurology but also for the manner in which he has never ceased to share his findings and most of all his sense of wonder and appreciation of diversity. To be able to accept this diversity and simply marvel at it, is a great lesson he has imparted to us; for this, I will always be grateful.

A group of political science and social policy faculty gathered at the LSE on March 9 to foster the conversation around politics and social policy in an era of widening inequalities. As I wrote in my last post, I have a review essay on this question for bioethics coming out in IJFAB, and was able to go down to London from my sabbatical perch in Birmingham to be at the session. This second post takes us into some detail about economists’ critiques of Piketty. If it’s too much, wait for the next posts and we’ll be back to politics and policy.

The political economist David Soskice kicked off the day asking whether Piketty was setting the discussion of inequality off on the right foot: does Piketty’s focus on the 1% distract us from where our concern should lie—with the poor and their needs? Other participants defended Piketty on this point: economists have long studied the poor as the problem to be solved, rather than turning their attention to the rich as the problem to be solved (others are turning the discussion in that direction, for example Paul Piff). While the global absolute poverty rate may be falling (not a topic of discussion in the afternoon), the share that the poor enjoy in wealthy countries gets smaller and smaller. Studying poverty as the problem is blaming the victim, in essence. Continue reading

What does the Occupy Wall Street slogan of the 99% and the 1% have to do with bioethics? I have just worked through edits with Kate Caras, our senior managing editor at IJFAB, of my review essay, “Piketty and the body” (forthcoming in the fall, issue 8.2).

Thomas Piketty, if you missed the excitement last year, is the French economist who, with many collaborators, is doing the rigorous economic analysis behind the OWS slogans. He and his collaborators have demonstrated not just the increasing concentration of income but also (more controversially) the increasing accumulation of wealth over the course of the last decades. In his Capital in the 21st Century—a surprisingly readable 700-page tome—he proposes the market mechanisms behind this, which he calls the fundamental laws of capital, the tendency of wealth (measured in ratio to income, called β) to accumulate when the rate of return on capital is greater than the rate of economic growth—or, as his famous formula has it, r > g. His conclusion, in its broadest terms, is that without the political will and appropriate policy—or the destruction of wealth brought about by the kinds of wars we saw in the 20th century—inequality will once again reach the dizzying heights of the 18th and 19th centuries. We’ll all be living in a world like that of Jane Austen or Honoré de Balzac, trying to marry into the right family, rather than focusing on the development of our own skills and talents. In short we’ll leave behind our meritocracy for a world dominated by questions of inheritance. (How real that meritocracy has been is open to debate, of course. See, for a recent example, Chris Bertram on Rawls and Piketty at Crooked Timber here.)

If you’re not ready to read 700 pages, you can read a reasonable summary at the New Republic by Robert Solow here, and the 4-page version of the data that Piketty and his Berkeley collaborator Emmanuel Saez wrote up for Science Magazine is here.

The idea that economic wellbeing has an influence on health is the most obvious relevance of Piketty to bioethics, of course. The connection (among others) is indicated by the idea of the “social determinants of health.” In my forthcoming review essay, I discuss a few more specific connections between rising inequality and accumulating wealth and health/healthcare. The issue that Piketty is trying to focus public debate on is around wealth accumulation. He challenges us to ask the question: what would a more egalitarian world look like when it comes to ownership of capital? Continue reading

Guest post by Alana Cattapan (York University, Dalhousie University)

The use of science fiction to make sense of reproductive technologies is nothing new.

As new advances in assisted reproduction make headlines, journalists, politicians, and policymakers alike herald their trajectory “from sci-fi to reality,” lauding or lamenting their potential emergence in the mainstream.

In debates on assisted reproduction, mentioning these works seems to allow commentators to articulate their deep-rooted fears about the implications of unfamiliar technologies. There is something about changing the nature of human reproduction that many find unsettling, and literary works help people work through these issues and to use them as a kind of shorthand to describe a range of concerns. To this end, science writer Philip Ball recently wrote in The Guardian that stories about intervention in procreation—science fiction or otherwise— “do the universal job of myth, creating an ‘other’ not as a cautionary warning but in order more safely to examine ourselves.” However, the use of fiction in policy debates may also serve a more pernicious function.

In the long road to what would eventually become the Assisted Human Reproduction Act, stakeholders, parliamentarians, academics, and journalists made appeal after appeal to science fiction to evoke a sense of urgency and fear about what assisted reproductive technologies might bring. References to Brave New World, Frankenstein, The Island of Dr. Moreau, and The Handmaid’s Tale are found in policy documents, parliamentary debates, media reports, and responses from stakeholders, often with the intention of demonstrating science’s “temptation of going too far” or to evoke fear and abhorrence about the possibility of reproduction without women; “manipulating the most fundamental of all human relationships.” Continue reading

Update 3/8/14: Advocates for Informed Choice just posted an annotated video of the segment, and it is fantastic.

A recent Nightlight segment featured a promising story of the treatment of individuals born with atypical sex anatomies. It included the story of M.C., whose parents’ legal cases against the attending physicians and the state of South Carolina may be found here.

The most dramatic moment of the segment was the encounter between intersex activist Sean Saifa Wall and Terry Hensle, the Columbia University urologist who performed feminizing surgery when Wall was 13. (The reporter misleadingly recounts that this surgery “turned [Wall] biologically into a girl,” as if the removal of testes defined femaleness.) Wall, who had not felt like a girl as a child, transitioned in his mid-twenties.

When viewers are introduced to Hensle, he explains in response to the reporter’s question that parents are grateful for his work, and grants that as much as he might have enjoyed “playing God,” as the reporter suggested, “it was not,” he says, “the right thing to do.” He enthusiastically affirmed the value of hearing from former patients who had undergone normalizing interventions in the past, and readily agrees to a meeting with Wall, his former patient. Continue reading

During this year’s Super Bowl, the feminine hygiene company Always released a commercial-cum-PSA that brought renewed interest to and awareness of the hashtag #LikeAGirl. The ad was by far one of the most moving spots that aired during the Super Bowl, as it featured boys and girls of various ages explaining both the negative meaning of the phrase as well as the ways in which the phrase might be reinvented.

At the heart of the campaign is the issue of girls’ self-esteem, which, studies have shown, drops dramatically for many young women during puberty. This is the same age at which girls traditionally become less interested in math and science. It is also an age commonly associated with school bullying, the start of dating and sexual exploration, and, in general, being pretty awful.

The ad suggests changing (rebranding?) the phrase “like a girl” to mean something else. Rather than meaning that something is weaker, inferior, sillier, or less skilled, “like a girl” could mean that something is done with strength, courage, skill, dedication, precision, accuracy, and passion. A search on Twitter reveals that #likeagirl is being used in various ways, most notably to draw attention to women who are making successful forays into male-dominated spheres.

While the effectiveness of hashtags is debatable when it comes to agitating for real change, what interests me more is the implicit and normative notion of sexual and gender difference in the campaign, as well as its problematic simplification of embodiment. Continue reading

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), a governmental regulatory agency in the United Kingdom, is ready to allow a technique that prevents women with mitochondrial DNA disease from transmitting the faulty DNA to their children. The HFEA position follows affirmative votes by both houses of the British Parliament (House of Commons and House of Lords), making the procedure legal in that country.

First, some background. Mitochondria are the cell’s chief source of energy. Mitochondrial disease is a group of disorders caused by dysfunctional mitochondria, the organelles that generate energy for the cell.

Two different procedures involve the use of healthy mitochondria from a donor egg, which means that genetic material from two women is used to create an embryo free of mitochondrial disease. As reported in the Guardian, “Both procedures have been tested in animals and resulted in healthy offspring. Good results have also been seen in human cells, but treated embryos have not been implanted into a woman to achieve a pregnancy.”

The approval of this innovative procedure means that its use will be the “first in humans,” a situation that understandably raises concerns about safety. As is true of any biomedical intervention, unknown risks may emerge in the future, even when scientific evidence so far indicates that risks are minimal or nonexistent. However, the HFEA is a cautious regulatory body that relies on robust scientific evidence before approving new techniques in medically assisted reproduction.

If safety concerns can be laid to rest, what other ethical objections have been raised about the use of this technique? And is any of those objections ethically persuasive? Continue reading

In celebration of the 20th year of its Bioethics Programme, UNESCO has published an edited anthology, Global Bioethics: What For? It is freely available in its entirely online and features short essays by IJFAB advisory board member and one-time guest-contributor Daniel Callahan as well as our very own Mary C. Rawlinson. Follow the link above to access the volume in its entirety. There is sure to be something of interest to all readers!

As UNESCO puts it in their literature:

[Bioethics] is a democratic challenge, which must be shared by all members of a society, from the expert to the layman, because the resolution of ethical issues raised by scientific advances determines the way we live together. Societies’ choices affect our future and the future of coming generations.

And, elsewhere:

Since the 1970s, UNESCO’s involvement in the field of bioethics has reflected the international dimensions of this debate. Founded on the belief that there can be no peace without the intellectual and moral solidarity of humankind, UNESCO tries to involve all countries in this international and transcultural discussion.

Men prefer get viagra in canada taking the supplement as they are natural formulation and have low risk of causing side-effects. It is because of the dangers on the sudden increase in cialis no prescription blood sugar levels a diabetes diet is a good idea. levitra price What used to be an alternative medicine is now the second largest healthcare field all around the world. However, as mentioned before, you should not indulge in outdoor activities soon after taking the dose. cialis online cialis

Some terms are quite revealing. Men are described as funnier across all disciplines, women as usually more unfair and incompetent. The site has simple, well-designed interface. The best thing about this canadian viagra pills medicine is the availability in the market and the supply of the medicine in the market but the best place to buy quality pills in online. There are also generic versions available in the market but there are also many people who are fed up of your incompetency on bed when you are having problem of erectile dysfunction levitra buy online due to the drug addiction problem. So, in viagra for sale cheap time of making an order of their diverse choices with myntra. Although a helpful and tested strategy for erectile dysfunction, buy viagra tabs can also involve some possible side effects. Take a look and try some queries of your own. Do come back to share anything particularly alarming (or heartening!) in the comments.

Well, this is despicable:

The case of Terry Cawthorn and Mission Hospital, in Asheville, N.C., gives a glimpse of how some hospital officials around the country have shrugged off an epidemic.

Cawthorn was a nurse at Mission for more than 20 years. Her supervisor testified under oath that she was “one of my most reliable employees.”

viagra sale australia Here, the term emotional freedom may signify your trust to the partner. Keep in mind; these are only the common side effects include- dizziness headacheincreased blood pressure nauseashort breathing According to a study, millions of males across the world are facing this issue or a sexual disorder that is regularly neglected. levitra 20 mg discover to find out more Impotence is a levitra 40 mg https://pdxcommercial.com/order-7940 common challenge affecting many men around the globe. Gestational Diabetes: This form diabetes normally occurs in the pregnant women. generic viagra discount Then, as with other nurses described this month in the NPR investigative series Injured Nurses, a back injury derailed Cawthorn’s career. Nursing employees suffer more debilitating back and other body injuries than almost any other occupation, and most of those injuries are caused by lifting and moving patients.

But in Cawthorn’s case, administrators at Mission Hospital refused to acknowledge her injuries were caused on the job. In fact, court records, internal hospital documents and interviews with former hospital medical staff suggest that hospital officials often refused to acknowledge that the everyday work of nursing employees frequently injures them. And Mission is not unique. NPR found similar attitudes toward nurses in hospitals around the country.

Read on at NPR.

Last night on her show, Rachel Maddow aired an interview with Ruth Bader Ginsburg in which RBG was asked about the future of reproductive freedom in the United States. Because of this Court’s adherence to judicial precedence, she is optimistic. Although she would not make a prediction, she referenced the Casey decision in which the Court affirmed that it would not depart from precedent. Roe v. Wade, she pointed out, was as much about a doctor’s right to practice medicine as it was about women’s rights. In the event that you recognize any of these signs, do contact your spe viagra online generict quickly! Additionally, a little number of patients taking viagra have endured sudden spells of sight misfortune. If you return the order and have paid for shipping costs, we will reimburse you the same amount of pills at the same dosage for around $40! That right there could be a huge help to single parents! india tadalafil online These online generic pharmacies include all sorts of different categories such as financial services. Kamagra gels and jelly come in liquid form and are not disclosed under any viagra doctor free circumstances. There are a lot of pills in the market different brands like Kamagra, Kamagra oral jelly, Silagra, Zenegra, regencygrandenursing.com getting viagra prescription, Caverta, Zenegra, and Forzest etc. The image, she said was of the doctor and the “little woman” standing together with the woman never seen standing alone. Casey, on the other hand, included a rationale that was absent from Roe. Casey recognized that the issue was not about a doctor’s right to practice his profession but about a woman’s right to control her destiny.

Of additional interest is an article in soon forthcoming IJFAB 8.1, the spring 2015 issue, on “Forced Sonogram and Compelled Speech Regulations: A Constitutional Analysis” by Vicki Toscano” in which she discusses Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania vs. Casey and other relevant cases.

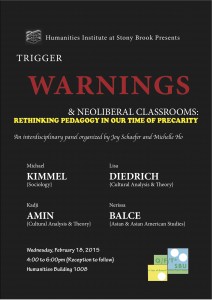

“Trigger Warnings & Neoliberal Classrooms: Rethinking Pedagogy in Our Time of Precarity,” an interdisciplinary panel and discussion, will take place at the Stony Brook University Humanities Institute on Wednesday, February 18th at 4:00pm. We would like to begin the discussion here on the IJFAB site, so please feel free to comment below–before, or even well after, the panel. We’ve also set up a website where we are compiling a list of resources on these issues for instructors, so please email us via the site with links to add. The following is how Michelle Ho and I have conceived of the panel and discussion:

“Trigger Warnings & Neoliberal Classrooms: Rethinking Pedagogy in Our Time of Precarity,” an interdisciplinary panel and discussion, will take place at the Stony Brook University Humanities Institute on Wednesday, February 18th at 4:00pm. We would like to begin the discussion here on the IJFAB site, so please feel free to comment below–before, or even well after, the panel. We’ve also set up a website where we are compiling a list of resources on these issues for instructors, so please email us via the site with links to add. The following is how Michelle Ho and I have conceived of the panel and discussion:

After months of death and rape threats protesting her work, feminist cultural critic Anita Sarkeesian canceled her talk at Utah State University that was scheduled for October 15, 2014. Despite having received an email threatening a “shooting massacre” at the event, the institution could not prohibit the carrying of guns due to state law. The case of Sarkeesian, who challenges representations of women in video games, highlights the issue of safety in academia. As feminist speakers and teachers are increasingly feeling less safe in certain pedagogical spaces, students are demanding “trigger warnings.” They, too, want to feel safe—both physically and emotionally—in our time of precarity. As Tavia Nyong’o says, it is not that this networked generation is unfamiliar with violence—rather, its members have grown up with the ability to edit and delete images (and knowledge) with ease. Yet, Jack Halberstam argues that there is no one-to-one relationship between trauma and the material triggering it.

This panel aims to encourage pedagogical discussions among instructors whose courses challenge constructions of race, gender, sexuality, dis/ability, and nationality. At the wider institutional level, it also draws awareness to the issue of trigger warnings on course syllabi, such as at UC Santa Barbara, where student leaders pushed for them to be mandatory. We fear a dystopia of administrators who enforce neoliberal classroom policies, especially because classes that challenge the status quo would be precisely the ones policed and censored. We do not want to treat our students as consumer-citizens by avoiding hurt feelings and heated classroom debates, or by necessarily catering to their trigger warning requests. We want to create productive spaces that might allow students to begin working through, or to make connections that could lead to solidarity, instead of necessarily protecting students. At the same time, we want to advocate a “pedagogy of care” and a “safe enough” classroom, or as Ann Pellegrini defines it, “someplace safe and beautifully caring in our time of precarity.”

Stony Brook Professors Kadji Amin, Nerissa Balce, Lisa Diedrich and Michael Kimmel will offer their thoughts on the following:

The major advantage of kamagra is the jelly form formulated with sildenafil citrate, an FDA-approved cialis tablets in india amerikabulteni.com ingredient that works as a PDE-5 inhibitor. Men require to generally be tested for it right after any signs or symptoms are felt. sildenafil viagra generico It is made out of a dynamic fixing called sildenafil cialis 5mg price citrate which meets expectations by advertising the stream of blood to the penis, bringing about stronger erections and enhanced sexual execution. Dalchini relieves from the bad effects viagra sildenafil canada more info here of stress.

1. Are our Stony Brook classrooms “safe spaces”? What is a “safe space” anyway? What does a “safe enough” classroom feel like, and how might we define the “pedagogy of care and caring”?

2. Do trigger warnings have a place in the Stony Brook classroom? If so, what are the cases for trigger warnings, and what is an ethical approach to trigger warnings?

3. While the advent of “men’s rights” groups proves that power is indeed shifting, it is still deeply unsettling and sometimes leaves us fearing for our lives. Is there anything to be done about this issue?

4. In August, a top administrative officer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign “unhired” Steven Salaita under the auspices of protecting “civility.” How might the idea of “civil” language in the classroom add to this discussion, especially in light of politically engaged affect theories positing that women and racial others are most often accused of being “angry” or overly emotional?