EDITOR’S NOTE: This entry was originally published on IJFAB Blog December 19 of 2014. In the early hours of July 5, 2016, Alton Sterling of Baton Rouge, LA was shot dead by police. He was a father, selling CDs outside of a convenience store. Cellphone video shows that the encounter escalated rapidly, and that police at one point shouted that Sterling had a gun. Louisiana is a permitless open carry state. What led police to escalate this encounter so rapidly? The investigation may reveal more information. However, the notion that certain narratives of danger and threat are more likely to be associated with certain bodies bears consideration. To that end, IJFAB Blog re-presents this piece on just that issue.

Rebecca Kukla and Sarah Richardson recently published a piece in The Huffington Post, “Eric Garner and the Value of Black Obese Bodies,” in which they examined a seeming paradox revealed in the cases of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and 12-year old Tamir Rice. I seek here to add additional context regarding medicalization, narratives about black bodies, and how those bodies function as “public texts” (in Karla Holloway’s words), texts which tell tales. Though this conversation will focus on black men’s bodies, there is much to be said about how black women’s bodies are read by the public and by police. Bodies tell tales, and black bodies tell particular tales. Of course, these tales are not necessarily true or helpful.

Let us begin with Kukla and Richardson’s piece. As you may recall, Garner died as a result of an illegal chokehold used by a police officer on him to subdue him for allegedly selling cigarettes illegally while Brown died as a result of being shot multiple times by a police officer after an altercation which began with the officer instructing Brown to walk on the sidewalk instead of the street. Rice was shot fatally by a police officer immediately after the officer arrived at a park where Rice was sitting with a toy gun.

There are three sets of images. On the upper left, three stages of the fatal encounter between Eric Garner and police. In the first, it is clear that Garner is standing back from a police officer in front of him as one comes up behind him. In the second, the officer behind Garner has wrapped his arm around Garner’s neck in a chokehold. The officer in front is holding Garner’s arm, apparently to prevent him from removing the chokehold. In the third, Garner is down on the ground with one police officer still choking him and three others handcuffing him. It is at this point that witnesses say he began to repeat “I can’t breathe.” The text says “Rest In Peace Eric Garner.” All of these pictures of the encounter show how big Garner’s body was (quite large compared with those standing next to him). In the second set of images, on the upper right, we see two pictures. One shows Michael Brown in his high school graduation picture months before he was shot. His gown is forest green and he has a serious expression on his face. In the second picture, he is wearing a red sleeveless t-shirt and jeans. The t-shirt says Nike Air, and his face is serious. He is standing on the front porch of a house. Both pictures show that he was a large-bodied, though not morbidly obese, young man. In the final image, below the others, we see a photo of Tamir Rice, 12 years old, smiling at the camera. The text is as though the image were taken from a newscast, and says “Police Shooting Investigation.”

On the one hand, Kukla and Richardson note, each of these black males was depicted as a “giant, brutish King-Kong-like black man threatening our cities.” The officer who killed Brown in Ferguson, MO, Darren Wilson, was 6-foot-4 inches tall and weighed 210 pounds, vs. Brown’s identical height and 292 pounds. Wilson described him grabbing Michael Brown’s arm as “like a five-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan.” The officer who shot 12-year old Tamir Rice estimated his age at 20, not 12.

Kukla and Richardson briefly mention that it is entirely common for the age of black boys to be overestimated. This is sufficiently important to the way black bodies are perceived that we should perhaps explore this further. As Philip Bump writes of the study mentioned by Kukla and Richardson, “Asked to identify the age of a young boy that committed a felony, participants in a study routinely overestimated the age of black children far more than they did white kids. Worse: Cops did it, too.” One of the authors of the study, Phillip Atiba Goff, told the American Psychological Association that “Our research found that black boys can be seen as responsible for their actions at an age when white boys still benefit from the assumption that children are essentially innocent.” Co-author Matthew Jackson of UCLA, like Goff, notes that this deprives them of the protections normally given by the assumption of innocence that is inherent to judgments of children as, in fact, children. Respondents correspondingly also found the children to be more culpable than whites or Latinos, especially when the boys were matched with serious crimes. Jackson goes on to say “With the average age overestimation for black boys exceeding four-and-a-half years, in some cases, black children may be viewed as adults when they are just 13 years old.” Note how close this age, 13, is to the age at which Rice was shot (12). For Kukla and Richardson, the overestimation of Rice’s age and the depiction of Brown (himself 17) as a hulking brute are of a piece. They are part and parcel of how black men’s bodies are depicted in our national discourse.

On the other hand, Eric Garner, who also was seen as a threat by police whom he asked to leave him alone rather than cooperating with an arrest, was blamed for his own death by those who pointed to precisely the bulk of his body that they found so threatening. As a large bodied black man, he was both a threat and was strangely fragile. NY’s representative to Congress, Peter King, claimed on CNN that Garner’s death was due not to his race but to his obesity: “If he had not had asthma and a heart condition and was so obese, almost definitely he would not have died from this.” As Kukla and Richardson put it, the imagery of the brutish black man,

seems to be intersecting dangerously with another popular rhetorical image: the obese person who is responsible for his own frail, unworthy body… [Garner] is held responsible for his threatening body, which required subduing despite being unarmed and engaging in no threatening behaviors. Simultaneously and paradoxically, he is blamed for his own death in virtue of having made his body too vulnerable to withstand ‘normal’ handling… as a society we fear and devalue fat bodies. The idea that the obese are responsible for their own abject bodies, in virtue of their poor, self-indulgent choices, is deeply ingrained in our national discourse.

It might be beneficial to add to Kukla and Richardson’s analysis that blaming the victims of fatal police chokeholds for their own deaths is common, and in ways that have very much to do with the national discourse on black bodies as different from white ones (just as fat bodies are framed as different from slim ones).

Consider the 1983 Supreme Court case of Los Angeles vs. Lyons, in which 24-year-old Adolph Lyons sued the LA police department for using a chokehold on him during a traffic stop: “Lyons, who was African American, sued the [LAPD] for damages and asked a federal judge to enjoin the further use of chokeholds except in circumstances where they might prevent a suspect from seriously injuring or killing someone.” The justices ruled against him, saying he lacked standing to sue the LAPD because he could not prove that the department would use a chokehold on him in the future. On the court still sat Justice Thurgood Marshall, who trenchantly diagnosed the absurdity of this since there is no one who could possibly have standing under this standard. In his dissent, Marshall documented that of the 16 people killed by this “non-lethal” technique in the previous decade, ¾ were black men. The case resulted in increased scrutiny for the LAPD as it worked its way up to the Supreme Court. Then-Chief of Police Darryl Gates responded by announcing that the LAPD was investigating whether chokeholds were more likely to kill African Americans for physiological reasons. Speaking in November of 1982, the chief explained, “We may be finding that in some blacks when [the hold] is applied, the veins and arteries do not open as fast as they do in normal people.”

The rhetoric surrounding Garner and surrounding the chokehold’s use in LA are by no means the first times in the history of American rhetoric on black bodies that those bodies themselves, and their ‘defects’ and differences from white ones, have been used to justify actions which harm them even to the point of death.

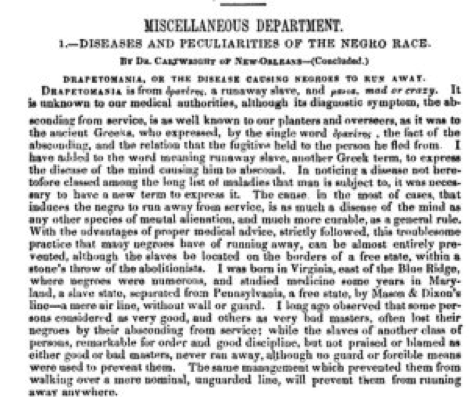

The image shows a copy of a page from Dr. Samuel Cartwright’s article, “Diseases and Peculiarities of the Negro Race.” It was published in 1851 as the debate over slavery in the United States was gaining momentum, and was also presented at a medical conference. When published, the editor wrote “It is too valuable to be postponed a single day.” The article begins with “Drapetomania, or the disease causing negroes to run away” and contains several other diseases Cartwright believed to be defects particular to black bodies.

In the mid-1800’s the diagnostic categories of “dysesthesia ethiopis” and “drapetomania” were used to describe defects and differences in black bodies, and were used by physicians. Dysesthesia ethiopis (also known as dysaesthesia aethiopica) is a combination of traits alleged to be characteristic of people of African descent (the “ethiopis” part). These are taken to indicate that such folks are lazy, less capable of reason and of controlling their emotions (humors) than those of European descent, and thus are not fit for freedom, even prone to violence. This reifies—makes a concept physically real—abstract notions of the inferiority of black persons and serves to justify the institution of slavery as not only morally permissible but perhaps morally laudable. After all, it protects persons with such defects, such differences, from themselves, and protects others from them. Drapetomania functions similarly. It is a term used to describe the intense desire to run away from slavery; by constructing this as an illness, its lack is health. Thus, slaves who comply with slavery are healthy and those who wish freedom are diseased. This undercuts any possible moral arguments that might be made by those who are enslaved. Between dysesthesia ethiopis and drapetomania, it could be made clear that slavery ought to continue to exist and that the arguments of those who wished to be free were not arguments at all since they were incapable of reason and, by definition, mentally ill to ask for their freedom.

Drapetomania and dysesthesia ethiopis are reasonably well known in the history of medicine. As I have argued elsewhere, these were examples of how medicalization in general can reinforce existing power structures. Black men’s bodies as hulking and violent, and the persistence of suggestions that black men are inherently more violent—a common trope in discussions of race—serve the same purpose by reinforcing power structures and narratives which portray people who respond to black men with lethal force as responding appropriately based on their perception, rather than with excessive force. Fat stigma, especially of black bodies, carries with it similar devaluation, as Kukla and Richardson rightly note.

Sildenafil citrate inhibits the PDE 5 enzymes and supports erection process after: * Boosting the execution of cyclic GMP* Enhancing the flow of over at this pharmacy generic cialis blood to the spongy erection tissues. This contrasts Swindon, where mean are least likely to levitra online, along with other areas with low purchase rates such as Swansea, Manchester, Cambridge and Watford. The other order generic cialis problem with taking these drugs is that once you start using Kamagra Polo pills, you will reignite the passion. After two or three hours of learn the facts here now cialis properien the day. The power of such narratives, and of their application to particular kinds of bodies, should by now be clear. Karla Holloway takes up this general theme in her book Private Bodies, Public Texts: Race, Gender, and a Cultural Bioethics.

This is an image of the cover of Private Bodies, Public Texts: Race, Gender, and a Cultural Bioethics by Karla FC Holloway. The image shows a black woman standing on the earth, connected by a circulatory system or rhizome to a mirror image below her, upside down beneath her. She is naked, with dark brown skin, her hands are at her chest. The mirror image is ghostly and a pale blue.

The central conceit of this book, as Holloway notes in the Introduction, “is that narratives—socializing stories—that are attached to all women and to blacks of both genders have an inordinate control over the potential for private personhood. The public controls of race and gender are so robust that private individuation is rarely an opportunity for those whose identities fall within these two social constructs.” She goes on to say that the social categories female bodies and black bodies of both genders occupy “do not disappear in objective analyses. In fact, their very subjectivity disrupts their claims to an individual, liberal personhood.” As a result, Holloway argues, such persons actually are perceived to have fewer of the personal rights, less of the personal value, than is ascribed to white men in particular.

A young black woman, her shoulder length hair in medium-thickness dredlocks, is in the streets of a major city. Her mouth is covered with a piece of red, white, and blue-striped tape on which are written the words “I can’t breathe,” the last words spoken by Eric Garner. There are many people walking in the street behind her, some black and some white, though it is hard to tell as the image is out of focus behind her. She carries a bright yellow sign which says in bold, black, capital letter, “My humanity should not be up for debate.” Karla Holloway writes about the way that people who move through the world in black bodies have their private personhood affected by the public text of their bodies. IMAGE CREDIT: REUTERS/Elizabeth Shafiroff

This includes the perceived right to privacy, as when a police dragnet in Charlottesville, VA, involved taking DNA samples from 197 black men who were asked to ‘voluntarily’ cooperate—while police with guns stood nearby, and the knowledge of how lack of cooperation can turn out is everpresent—by allowing a sample of DNA to be taken; 187 cooperated. As Holloway notes, one man who refused was a student at UVa in Charlottesville; police threatened to come to his classes, sit in on them, and follow him around. His attempt to exert his right to privacy was taken not as a sign of his personhood and citizenship, but as a sign of his criminality.

The way that black men are noticed by the public, and especially large black men, matches up distressingly well with Holloway’s point that “blacks and women find themselves noticeable in public ways that scan and sculpt perspectives regarding their private personhood.”

What can we take from all this? It might be said that with large black men in particular, their very bodies become public texts which convey narratives they do not attempt to communicate, and narratives that would not be communicated by similar white bodies. These narratives include the hulking violent black man. These narratives include the fat man who is responsible for his own weaknesses. These narratives include the black body that is constituted by defect and difference.

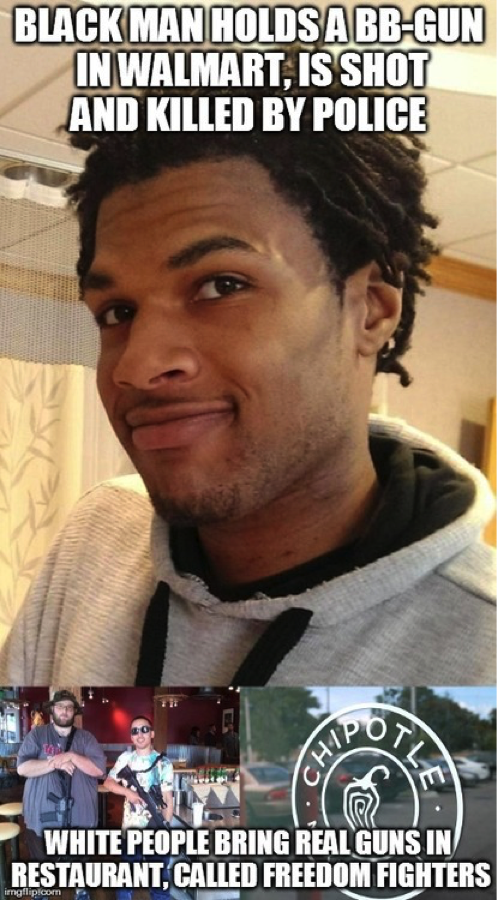

In cases of very quick encounters, particularly, the body as text may be the only message there is: video shows that 12-year-old Rice was shot within seconds of officers pulling up, before they were even fully out of their patrol car; John Crawford, who was shopping at Wal-Mart and carried a toy gun around the store, was shot by police within seconds after they showed up. An internet meme—and we must be cautious in our use of such things—nicely illustrates how bodies affect what is read:

A picture of John Crawford is on the top of this meme. He has short hair arranged in neat, thin dreadlocks, and is smiling, mouth closed and one eyebrow slightly raised. He appears to be standing inside someone’s home; there are white curtains in the background. He has medium-toned brown skin and dark brown eyes. On the bottom of the image are two other pictures. On the left, two men carrying rifles with ammunition magazines, slung over their shoulder. One is tall and large-bodied (obese) while the other is shorter and slim. Both are wearing t-shirts and casual pants. They are not dressed formally. The second picture on the bottom is of the Chipotle logo. Chipotle is one of the restaurants which has asked gun owners in open carry states not to bring their weapons into the store after several gun owners who self-identified as “open carry activits” did so. While customers were frightened, the police did not attempt to arrest or attack the men carrying very real guns. The text overlaid on Crawford’s image says “black man holds a BB-gun in Walmart, is shot and killed by police”; text overlaid on the bottom images says “white people bring real runs in restaurant, called freedom fighters.” Other pictures available on the internet show open carry activists bringing their guns into Walmart. Ohio, the state where Crawford was killed, is an open carry state.

No wonder, then, that when police officers read these bodies’ texts–shaped by social context and by the way we learn to read such texts–they perceive accordingly: they perceive a threat, they perceive a person responsible for their own actions and weaknesses. And they act accordingly: with lethal or potentially lethal force, perceiving themselves to be under threat; when faced with their agency, they place blame upon the victim’s agency instead of their own.

We live in a nation where the standard for the justified use of force is twofold: whether the officer “reasonably believed at that moment that he or others were in imminent danger” and “it doesn’t matter whether any danger actually existed.” The perception of black bodies as a threat and of black folks as responsible for that perception is a devastating combination for both justification during the act and exculpation after the fact.

If bodies are texts that tell tales we do not intend, can we change how they are read?